'Winter in Sokcho': the melancholy hits

#Scurf212: my old review of the 2021 brooding, noir, French novel that has now been made into a feature film

Elisa Shuan Dusapin’s spare novel Winter in Sokcho made waves with its subtle language and atmospheric setting when it was first published in France in 2016. In 2021, it published in the U.S. for the first time, and garnered praise for its brooding characters and pervasive ennui. Now as the world gears for the movie’s release, I thought of sharing my review of the book which was published in a now defunct magazine all those years ago.

WINTER IN SOKCHO by Elisa Shuan Dusapin, translated by Aneesa Abbas Higgins, reviewed by Anandi Mishra

With a strangeness at its heart—an anguished young woman feels the hint of a flame with a foreigner—Winter in Sokcho is one of the best literary noirs in recent memory.

It helps, too, that the book is written to be consumed in a single sitting. It’s a short novel, full of visually evocative and poetic considerations of love, language and connection. Winter in Sokcho begins and ends like dew drops in winter, collecting each night and evaporating the next morning. The story starts off with the unnamed narrator returning to her hometown of Sokcho from university in Seoul and taking a job as a live-in receptionist and cook at a rundown hotel, run by the crusty Old Park. She chafes at the love of her vacuous boyfriend, is in the doldrums about her job and doesn’t want to be around her mother. The inner life bleeds into the physical: “I had to stand in front of the mirror and pull out my eyelashes one by one until I could finally see myself again.”

The narrator is one of those female characters so often to be found in new fiction, to whom things seem to happen from a distance as she looks on, detached and unaffected. Also in line with a current trend in fiction, Dusapin explores not just the mind and soul of the protagonist,but also her body and eating habits. The narrator’s work in the novel is to protect herself from the emotions, feelings and affections of people who care for her. She chases after places like the sea, where nothing happens, drawn to the frigid corners of being uncared for, lonely and ignored.

I would walk out to the pagoda at the end of the jetty, skin clammy from the stench of the sea spray that left salt on the cheeks, a taste of iron on the tongue, and soon, the thousands of lights would start to twinkle and the fishermen would cast off from shore and make their way out to sea with their light traps, a slow, stately procession, the Milky Way of the seas.

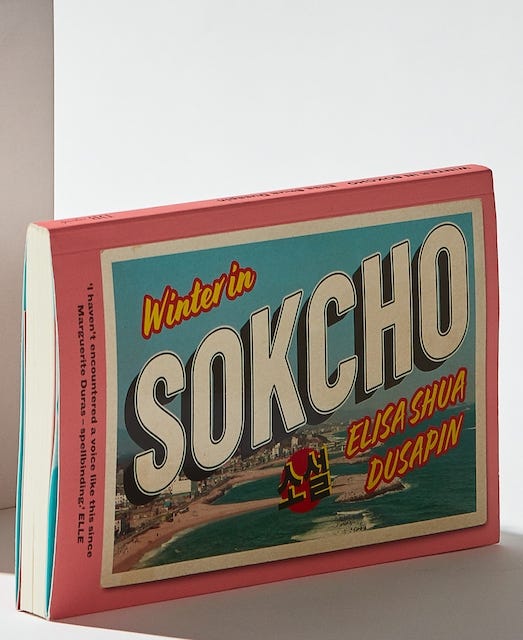

In the absence of definitive action on the part of the protagonist, the season of winter shines out as a formidable character, looming large in the lives of all the people. In ironic contrast to the novel’s summery postcard cover art, Dusapin’s evocative sentences conjure up a sense of melancholy and of beauty, which enchants even as it haunts the reader.

The unexpected arrival of French artist Kerrand at the narrator’s guesthouse spurs the protagonist on to an emotional journey, though he only takes a fleeting interest in her. With her help, Kerrand goes about the business of exploring the “authentic” Korea for his art. The protagonist, having studied French, takes interest when he talks of Maupassant, Monet and the “grey and dense” light of his native Normandy. For her, the 24-year-old whose French father deserted her when she was too young to remember, the contrast with Sokcho seems obvious: “You had to be born here, live through the winters. The smells, the octopus. The isolation.”

The protagonist embodies her physical body in a detached way, feeling occasionally intrigued by the bodily presence of the Frenchman: his artful habits, his mundane treatment of her, his interest in the city—and eventually her—touches off a complex set of emotions. Dusapin knows how to strike a balance, never overdoing it, but keeping the emotional swings subtle through her writing. Dusapin’s skill lies in capturing the attention of the forever distracted reader without trying. In not drawing much attention to itself, the poetic prose pulls the reader in: “The light was dimming too, blurring the contours of the room. I looked at the fish. The ink stain at the foot of the bed. In time that too would fade.”

Winter in Sochko delivers an unassuming but potent story that lingers. What is most riveting is the constant push and pull of language in the novel. Even though she is educated in French, the protagonist doesn’t interact with Kerrand in it. She feels like a cheat talking in English, confessing: “To be honest, my French was better than my English, but I felt intimidated at the thought of speaking it with him ... He didn’t need to know.”

This communication gap is typical. At the heart of Winter in Sokcho lie certain unanswered questions: Is the protagonist anorexic? Is she overweight? Is she depressed or just anxious? Is the Frenchman her father? We don’t get to the heart of these answers, but Dusapin is able to hold the attention of her readers because of the novel’s suggestiveness. With its serene energy, terse conversations, and unexpected viscerality, Winter in Sokcho conjures up a season I already wanted to revisit after laying the book down.