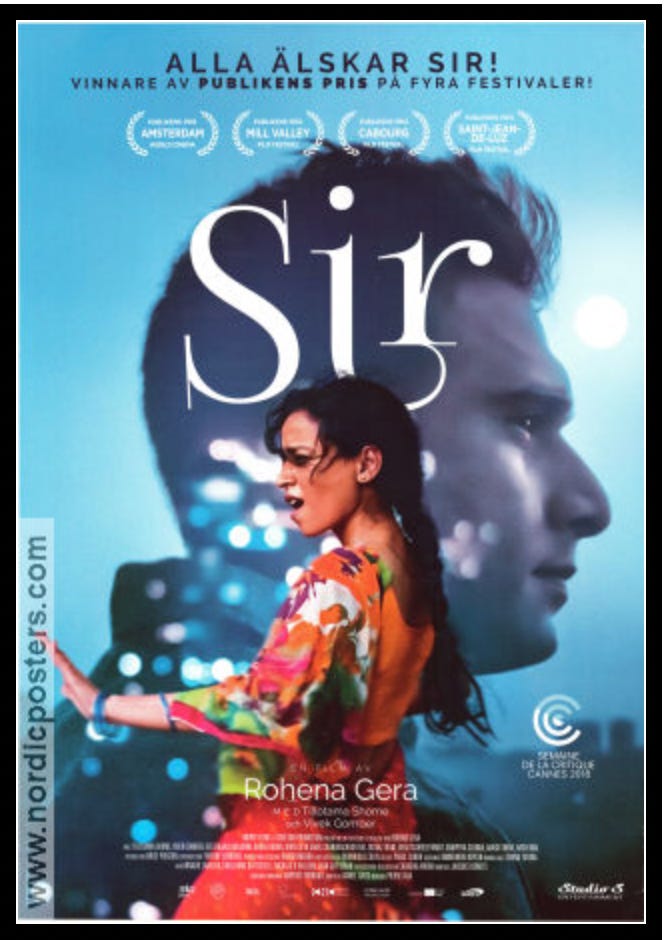

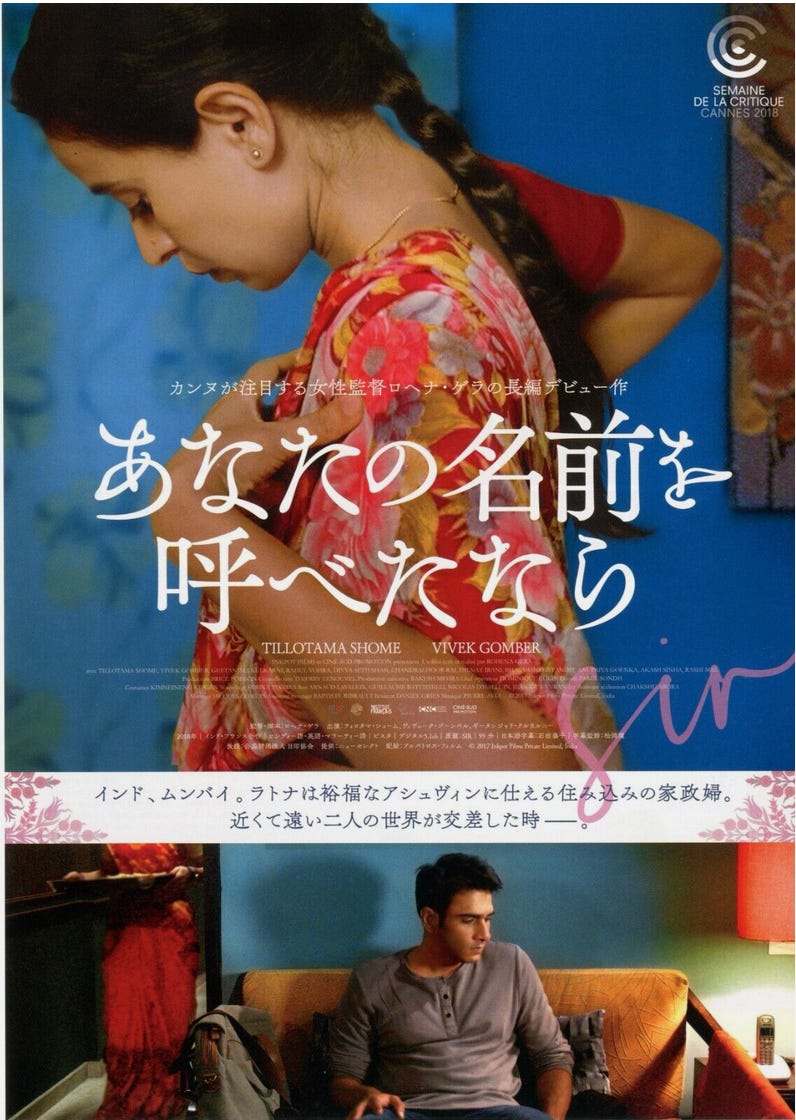

It began, as so many things do now, with a screen. A laptop, propped on the duvet, playing Rohena Gera's Sir, a film I’ve watched a handful of times since 2019. It’s a film of tight spaces, of the kind of intimacy born from enforced proximity: the sleek, modern apartment, a gilded cage; the broad, almost sculptural shoulders of Vivek Gomber; the quiet, relentless movement of Tillottama Shome through the kitchen, a space both servant and sanctuary. These elements press together creating a kind of elegant claustrophobia, a breeding ground for a desire that feels almost inevitable, yet still, somehow, illicit.

As Sir played on the laptop screen, burning slowly, flowing like molasses, I stole glances at the grey skies outside. It was drizzling, a kind of greyness taking over in the middle of this mid-March day. After I finished lunch, I looked up Shome’s Instagram and scrolled past her recent posts. To my surprise, they were from my side of the world — she is/was in Berlin, posting like a child full of glee about her sandwiches, and coffee. She had been on walks spotting lichen and snow-laced tree barks in the Grunwald (green forest) that surrounds the German capital.

That’s when I started daydreaming, that perhaps I could’ve been the one showing her around. Berlin, Frankfurt, Gothenburg. I closed Instagram. Her posts, the childlike wonderment in her captions, stayed with me.

I went back to Sir. Its the kind of film that keeps you and your wayward attention with it. By now I knew every line, every scene of the movie. Much like The Lunchbox had meant to me so many moons ago. A romance, a social commentary, a love letter to the kind of relationships that are usually thought of as frivolous, mocked, even illusory.

An unease permeates the city in Sir. One could picture Ashwin, without effort, amidst the clamor of a mall, a gleaming Apple Watch in hand, a symbol of his place. Ratna, meanwhile, would navigate the narrow, crowded lanes of the street market, searching for inexpensive bhaji, a familiar taste, a necessity, a world away from the cool, shared space of their urbane home. Beyond the wide, almost foreign expanse of the balcony, a space reminiscent of Singapore, the air itself feels heavy, a confluence of diesel, the sharp sting of nitrogen dioxide, the slickness of petrol, and the invisible, suffocating weight of PM2.5. The city, a palimpsest of contrasts, of unseen burdens, of lives lived in close, yet distant proximity. You can almost smell the air through the screen.

The house, in its largesse plays the character of an alienating, constantly supervising, inner (or is it external?) moral voice. It is big enough with ample room for both of them to not run into each other for hours, but it is also limited in its expanse with shared meeting spaces like the kitchen (where she cooks, while he gets a beer), the living room (where she dusts, while he lounges), the entry hallway (where, again, she receives each parcel dropped into the house, each guest or other fleet of domestic helps, while he just comes and goes).

The deep mahogany paneled walls, the ornate mosaic tiled floors, the sleek cabinet lined kitchen, the vast dinning table, the endlessness of the balcony where Ashwin sometimes hosts friends, but mostly just hangs out by himself — they scream of loneliness. A kind that is understood so well by anyone who has lived in the 21st century. A big city loneliness, but also a kind of dwarfing of the self that takes place when one has to inhabit a place where they’d rather not be.

Ratna, arranged her space, yes, with a kind of desperate precision. Trinkets, a vase, laundry, curtains, idols of Gods. Many walls run between these reticent love birds, walls of class, caste, economics, but also, insidious, invisible walls: silence, unspoken assumptions, invisibility. Ashwin, spectral, haunted. Ratna, rooted, insistent. The house then becomes not made of square footage, but of power — who occupies, who defines, who controls. An architecture of inequality (before Paradise).

At one point during the film Ratna shares that she lost her husband at the age 19, that left her as a social outcast in her own family. The coldness, and a wry smile playing on her lips, with which Shome delivers that scene makes one immediately realise about the double alienation Ratna has had to experience. With filmmakers increasingly focusing on large Indian cities or revisiting the overly familiar Hindi heartland, Ratna’s story becomes particularly significant. Her simple statement reveals how societal norms in Indian villages remain stagnant, despite the infrastructural, intellectual, and financial progress enjoyed by major cities. “You have to move on, there is nothing more to it,” she says, with a matter-of-factness familiar to anyone who has experienced similar circumstances.

When asked by Ashwin if she would’ve liked to be a “tailor” she corrects him, “fashion designer”, and this correction, or suggestion of her ambitious heart only makes sense — she has been saving for her younger sister’s exam fees and not her imminent marriage. In that moment, I scribbled into my Notes app: “Tillotama Shome’s acting in Sir and in every movie makes me want to be her best friend.”

While the script itself is sparse, the soundscape is delicious with melodies of the city traffic always humming along, the Ganpati dance music, the trill of fast moving vehicles on the street, the incessant honking interspersed with the idle barks of a dog, the soft cooing of the insides of a house, the tremor of coastal breeze on the balcony, the lilt of airplanes whizzing by.

In a way this music creates a soundscape for the audience, making us all inadvertent listeners not only to the very personal, intimate verbal exchanges between them, but also the other sounds that make up their inner lives. It also made me think that this movie could only have been based in Mumbai — what with Gomber’s gentleman-ly self, the restrain in Ratna’s character, the kind of nosiness with which Ratna’s colleagues try to intrude but politely back off when she doesn’t entertain them. Sir makes it singularly evident that is entirely possible to know places through their actual sounds, and that sounds make people, just as the places do.

There are hardly any missteps in the film, with almost everything slotted into its perfect shape and mold, just how sometimes, life can be. Sir has, in a way, taken the place in my heart that The Lunchbox once held. Both are inherently Bombay stories, filled with a hopeful, original, and profoundly real quality. They are the kind of films that offer perfect companionship, especially on days like today, when the rain falls steadily outside.

Following Ashwin and Ratna through the motions of their curt, limited exchanges, I closed my eyes and could imagine myself lying in a field surrounded by cicadas, in a far away open field outside the city, where the noises are yet to seep in, the sounds yet to take over — it’s just us. It was an intimate, far-fetched tableau: Ashwin, Rachna, and the audience (me), a silent, unseen collective, suspended in that liminal space between their world and ours.

Read my short note about The Lunchbox:

on watching The Lunchbox 🔁

*This essay was written in the summer of 2017, or probably early 2018, much before Irrfan Khan passed. I’m currently working one about him, I’ve been working on it since the day he left us. I hope I publish it sometime this year…