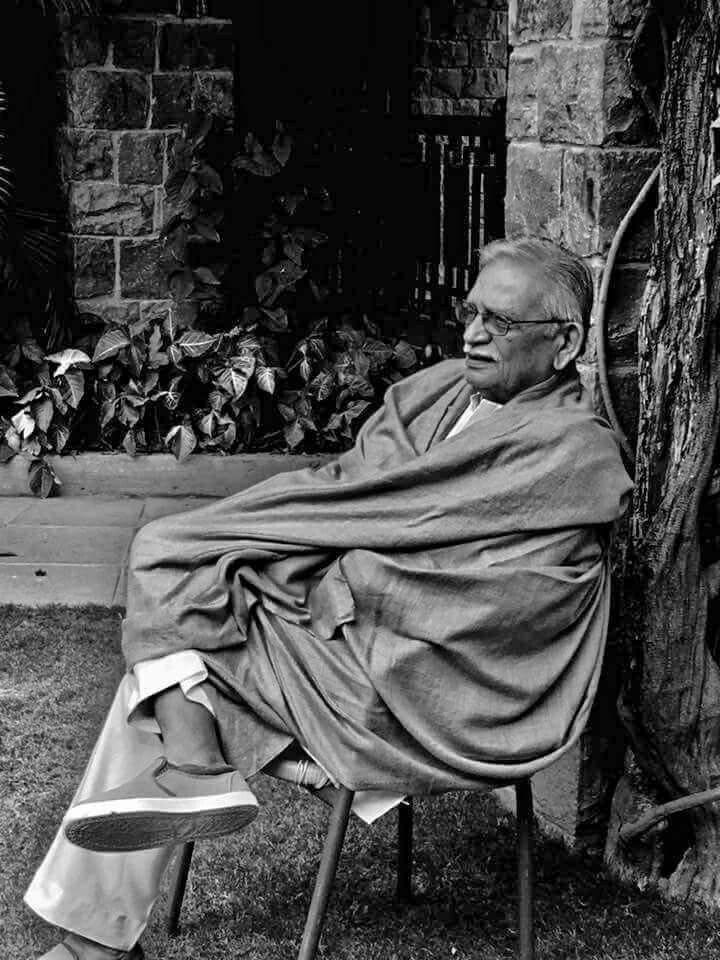

The endotic in Gulzar

#scurf222: Living should engage all senses, says Gulzar as does Georges Perec

Everyone who is remotely interested in Hindi songs from any era will have their own top three or five (even more) favorite Gulzar songs. The lyricist, now in his late 90s might’ve slowed down on the lyric writing front, but he’s given an entire generation enough fodder to drink in from the pools of. In his interviews with Nasreen Munni Kabir, which span various books, Gulzar has spoken vividly about evoking of all six senses to convey the essence of love. This is a broad essentialisation on my part, but I read those books in my Chennai college library more than a decade ago. While I might not be able to quote him verbatim, I’ve carried with me through these years his description of the writing process.

It was the monsoon of 2014, I’d just moved to Chennai for college, was a hopeless romantic, and was ready to acquire the esoteric knowledge of the field of journalism. I stupidly called the city Madras, walked barefoot by the Besant Nagar beach at midnight, found amusement in roasted corncobs and chilly pepper spiced mango slices bought from saree clad vendors at odd hours.

I was also weaning myself off the music I’d spent about half a decade listening to in law school — heavy metal, crust punk, death metal, rock, grunge. I was trying to pay attention to the city, this little college campus and the faces that bubbled up before my eyes. For this, I needed a sense of silence to be able to find the music in this new milieu. So naturally, Slipknot, Foo Fighters and Three Doors had to take a backseat and instead I allowed my senses to be assailed by AR Rahman’s Tamil songs, tracks from Bangalore Days, Neram and the likes. With a little help from batchmates, library and kitchen staff, I made my own algorithm. Slowly, I built a whole city in my head out of these songs. Brand new living in a brand new place where I heard multiple languages, different musical instruments (the saxophone, the violin, the flute, the (damn) guitar) that populated my varied, imagined mental topographies.

On days when it poured inexorably, and I missed the sound of my native tongue, Hindi, I’d find my way to the known comforts of Gulzar’s songs. I had up until then used his songs as my maps through the world but in that new culture, new atmosphere far away from everything I was familiar with, his lyrics opened themselves up to me in a new way. I was so strangely attuned to listening to music in just every other language than Hindi that when I did listen to, let’s say Yaaram or Mera Kuch Samaan, the fog of familiarity lifted. These songs while might be light or lacking in deep melody, unlike the Tamil and Malayalam songs of my choice, carried lyrics that made me sit right up.

As much as I wanted to sing along to the lyrics of Moongil Thottam I’d not be able to immerse myself completely — physically, emotionally, intellectually — in its waters. Gulzar’s poetry, on the other hand, felt like a throbbing, blooming Rhododendron waiting for me to just cast a glance at. What stood out then, in Yaaram is the resume-like quality Gulzar evokes through his words. Carefully crafted, or arrived at slowly, there’s a domestic inner world in his poetry. A trembling vulnerability.

And it’s the lyrics that lend a soothing sensuousness to the song picturized on an otherwise off kilter, soi-disant, immediately appealing throuple — Huma Qureshi, Emraan Hashmi, Kalki Koechlin. The song composition by Vishal Bharadwaj is light, floating at the surface, never really moving into the cerebral as that’s the job of the lyrics. A cozy, hippie, slightly buzzed vibe percolates the room as we hear a sultry Sunidhi Chauhan and equally affective Clinton Cerejo croon for Kalki and Emraan. My imagination lights up, setting off fireworks in the head as I comprehend the sheer possibilities that abound this frame.

To add to the fervor are Gulzar’s lyrics that are little jewels moving in complete sync with the chorus of the world around. That he finds poetry in the mundane is an ineluctable fact of history, but in this poem (because song feels like a lesser description) Gulzar rises above the mundane. He writes a lover’s resume. As if she’s proposing herself for the role of a lover in his life and hence detailing these little and big things she will be help him accomplish on a daily basis.

Hum cheez hain bade kaam ki… yaaram

Hamein kaam pe rakh lo kabhi… yaaram

(I’m a useful little something, dear one

Why don’t you hire me, dear one (translation mine))

Marooned in this grey-green, rainy city across the country, far from my everything I’d known, famished, needy and often high, I felt these words vibrate in my ribcage.

French experimental writer, filmmaker Georges Perec could explain what Gulzar does in his poetry. In his book An Attempt to Exhaust a Place in Paris, he sought to capture the small details that often elude us:

“Describe your street. Describe another street. Compare. Make an inventory of your pockets, of your bag. Ask yourself about the provenance, the use, what will become of each of the objects you take out. Question your tea spoons. What is there under your wallpaper? How many movements does it take to dial a phone number? Why? Why don’t you find cigarettes in grocery stores? Why not?”

Similarly, in Yaaram, Gulzar lays bare the itinerary of love, in the form of a poetic to-do list, or a bullet point of skills that this candidate has to offer for this position of being a lover. He writes:

Peechhe peechhe din bhar

Ghar daftar mein le ke chalenge hum..Tumhaari filein, tumhaari diary

Gaadi ki chaabhiyan, tumhaari ainakein

Tumhaara laptop, tumhaari cap, phone

Aur apna dil, kanwaara dil

Pyaar mein haara, bechara dil(Tiptoeing after you all day long

At home, in the office, I’ll carry with me…Your files, your diary

The car keys, your reading glasses

Your laptop, your cap, phone

And my heart, my feeble beating heart

My heart in love with you, my poor little heart… (translation mine))

Instead of making promises about bringing the grand (stars, moon, gardens and museums) at the step of the beloved, Gulzar promises the subtle pleasures of sharing the everyday domestic, lending it the air of unprecedented romance. The way you share a quiet, ordinary life with someone, and how that, in itself, becomes everything. It wasn't about grand gestures or illicit meetings on hidden terraces, no desperate rebellion against a city that didn't care. These lovers are regular ones, like you and me. Gulzar’s poetry describes his street of love, his ordinary plea of being a lover. That’s how you write about love, he seems to say. Not as a fever dream, but as a shared street, a quiet plea.

Yeh kehne mein kuch risk hai yaaram..

Naaraz na ho ishq hai yaaram..

Ho raat savere, shaam ya dopehari

Band aankhon mein le ke tumhe ungha karenge hum

Takiye chaadar mehke rehte hain

Jo tum na ho tumhari khushbu soongha karenge hum..

O… zulf mein phansi hui khol denge baaliyaan

Kaan khinch jaaye agar, kha lein meethi gaaliyaan

Chunte chalein pairon ke nishaan

Ke un par aur na paanv pade(There’s some risk here, lovely

Don’t be miffed, it’s just love

Be it day or night, dawn or dusk

I will carry you in my shut eyes, drowsing about

Pillows, bedspreads are perfumed

In your absence I will find your scent

I will loosen an earring tangled in your messy, long hair

In the process hurting you silly; you can call me names for that

I will spot and decorate your footprints

so no one steps foot on them (translation mine))

In here lies the urge to find the lover and proposition them in ways that are infraordinary, habitual, even the feted quotidian. Through this song, once again, Gulzar finds a new way to write about his observations on love by capturing the seemingly frivolous, small details of loving that often elude us. If you’ve been in a engaged, deep or even boring domesticity with someone you know that domestic spaces are emotional battlefields. Sometimes you ask them to hand over the car keys, the toilet roll, the soup ladle. You share spaces, sometimes reading two pages of the same newspaper, helping them zip up a dress, or fart in the same room. Gulzar, much like Keats, Shelley and Wordsworth, emphasises on cataloguing that which is not noticed, that which has no seeming importance. Gulzar writes “what,” in Perec’s words, “happens when nothing happens other than the weather, people, cars, and clouds.”

I’d be remiss not to mention one of Gulzar’s most loved ballads Mera Kuch Samaan here. The lyrics detail the exact itinerary of things that an estranged lover is asking her ex.

Mera kuch saman tumhare paas pada hai

Sawan ke kuch bheege bheege din rakhe hain

Aur mere ik khat main lipti raat padi hai

Wo raat bujha do, mera wo saman lauta do(You have some of my things, objects,

Those drenched monsoon days

That night enveloped in my letter

Douse that night, return my things, items (translation mine))

Yesterday… It was late, almost eleven, the summer light in Gothenburg still clinging to the sky, a pale, reluctant gold. I was in bed, of course, reading Perec – An Attempt to Exhaust a Place in Paris. His words, those detailed observations of a mid-October day in 1974, just unspooled in my head. The cat was asleep on the sofa, a dark, breathing lump, and the sky outside was turning that deep, crepuscular blue, like a lid closing over everything. But I wasn’t really there. I was with Perec, watching the blurry rush of people and buses, the gleaming Citroëns, the dogs, the umbrellas, all of it whizzing past the cafes and the tabac in Place Saint-Sulpice, half a century ago. It’s a longwinded way of saying that the ordinary, when you really look at it, when you really try to record it, can be astonishing.

I could quote Perec and Gulzar endlessly, in a world so obsessed with the one big moment, there’s solace to be found in this infra-ordinary. Perec calls it more than ordinary, as does Gulzar — the ordinary observed so closely, obsessed over slightly painfully, that it morphs into the transcendent, edging closer to life itself. I don’t know about you, but it feels important to me. Because it brings me closer to living and experiencing things, emotions, meals, conversations and life in a more wakeful state. It helps me calmly measure the sticky inventory of my everydays.

My small hours in low places, where time seems to have halted, this attention to the infra-ordinary opens up a third eye to see the mundane through. In doing so I feel my life ebb towards a sense of being complete and frankly, that’s all one needs on some days. Giving the fundamental elements of the everyday their own “meaning, a tongue, to let them, finally, speak of what is, of what we are.” Perec concludes, “What’s needed perhaps is finally to found our own anthropology, one that will speak about us, will look in ourselves for what for so long we’ve been pillaging from others. Not the exotic anymore, but the endotic.” And Gulzar gets it just right!