#scurf93: an ode to my elegiac hometown

The stench was everywhere. There were spaces of no hope, pockets of nothing, mounds of heap and dust and mud that greeted us all around. But what first got your attention was the open drains, leaking sewage pipes, and the still, stagnant water in them. Flies hovered over them, like exposed wounds chased by pain and blood. Then came the sight of pigs rolling in the slush pile. The numerous cows and buffalos would be a relief after this. And then there were the stray dogs who were the least of our problems.

The street on which my father’s house stood never saw a fully constructed road till about ten years back. The slimy ragpickers were always happy at the sight of no roads. It meant more people would drop their belongings unknowingly into the muck, and disgusted by the slime, would rarely bother looking for them.

Growing up in this neglected, erstwhile industrial city of Kanpur, in the early and mid-nineties had created some kind of a stilted perception of the world in my mind. And even after close to three decades in this country, I have realized that there is a luck with which some of us are born. Though I have moved out of that city which technically is my hometown, I am yet to understand the destiny towards which it is headed. With time things there have only grown progressively worse.

The heavy air smelling of rot had always cast its long shadow on all of us born there. It added to the general mood of the city — that of hopelessness, fear and muck. You could almost taste the dirt. The filth and grim creeping up on you in your dreams. Most of my roadside food memories now taste of odd, metallic rust, like blood.

It was not an abandoned town, no. It suffered from governmental neglect and forgetfulness. The roads were lined with what once were bubbling hotspots of employment. The city wore its closed down mills and factories as a badge of honor, a mnemonic relic from its glory days. The city was rendered ghostly, a mere shell of itself after these mills shut down. It was almost as if the color flew out of the windows, sucked into the deeply grey/yellow skies.

As a kid, I headlined a pack of boy-wild, uncontained, and ruthlessly rebellious girls in the neighborhood. My aunt would call me queen bee. We would run up and down the unlit, ruinous, strange roads in the area, playing hide and seek or tag. Everything was covered with the worst possible version of itself. Once I skipped and jumped over the low fence wall of our playground, and smack my palm landed on what was human excrement.

Growing up there we were used to the worst of all things. Today as I remember the place, my stomach turns with rancid hatred not because I belong from there, but because things have gone worse now. The city is now a patina of what it used to be, its own ghost. The drug pockets that had come up in the 60s and 70s had lent it some character, a distinct charm. But now even those have closed. No opium, marijuana or hash. Only cheap, contaminated liquor and American cigarettes.

In this city, there was often nowhere to go in the evenings. Dusty, smelly roads invited very few outings. The smell of leather and cow dung taking over the entire geography of the city, and by extension our senses. The ruins of the city were no archaeological ruins, they were not even poetic or ruminative. They were ugly, derelict and repulsive, a kind of ruin that invited neglect.

Sitting on the banks of the holy river Ganga, Kanpur could have worked at its bucolic charm, had it preserved its rustic beauty. But located on the western side of Uttar Pradesh in northern India, this city has steadily seen a downfall in all possible ways. When I was born, in 1991, the population comprised of residual aristocrats, intellectuals, and some loyal natives. Now over half the city’s population lives in abject poverty. Lack of education, public health and basic infrastructure have been handled with disinterest by a series of governments, all adding to the aura of forlornness.

Absent from Indian history until the 13th century, Kanpur became an important trade center during the colonial regime. In 1765 after defeating the Nawab of Awadh on the banks of Ganga, the British realized the strategic importance of the city and began to build mills. Leather, textiles and cotton became some of the major industries there, providing employment for almost all of its working class. The mills began to fall in the 1960s, and the last one closed in the 1990s. This is the story ever since.

I guess when you are born to a place of no hope, you start from nothing and you don't really have much to loose. Why then write about it at all? Perhaps that's why I don't.

My recent articles are here: https://anandimishra.contently.com/

Read and share.

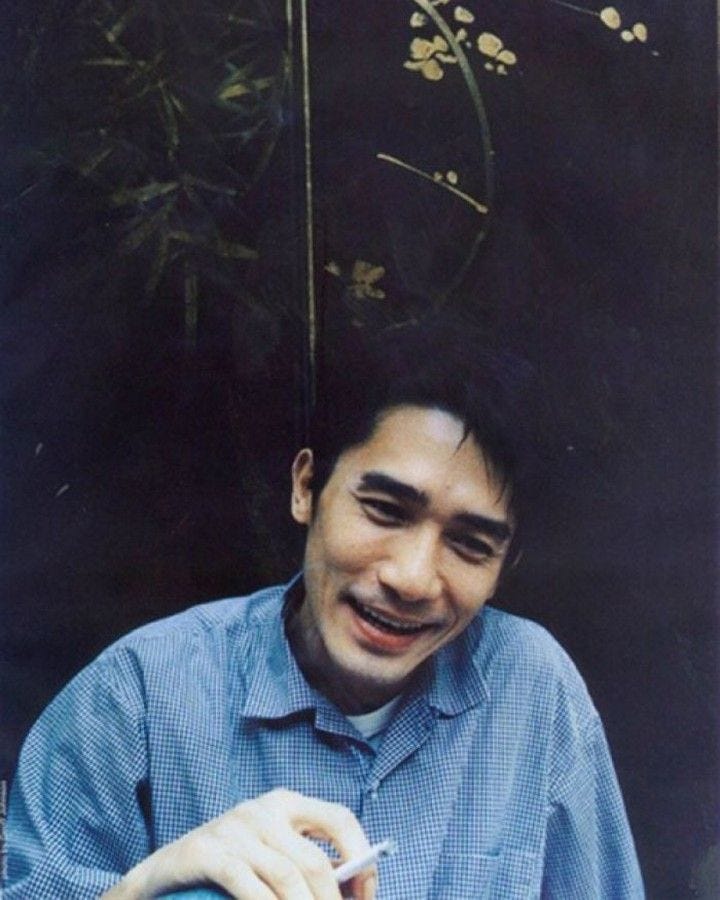

Signing off with a happy faced Tony Leung Chiu-wai whose birthday it is today

https://youtu.be/TXceE8x-9GA