#Scurf190: Conversation with Niamh Campbell

The Sunday Times Short Story Award winner on writing after childbirth, Dublin's welcome hipster gentrification and the vulnerability of being a young person in today's world

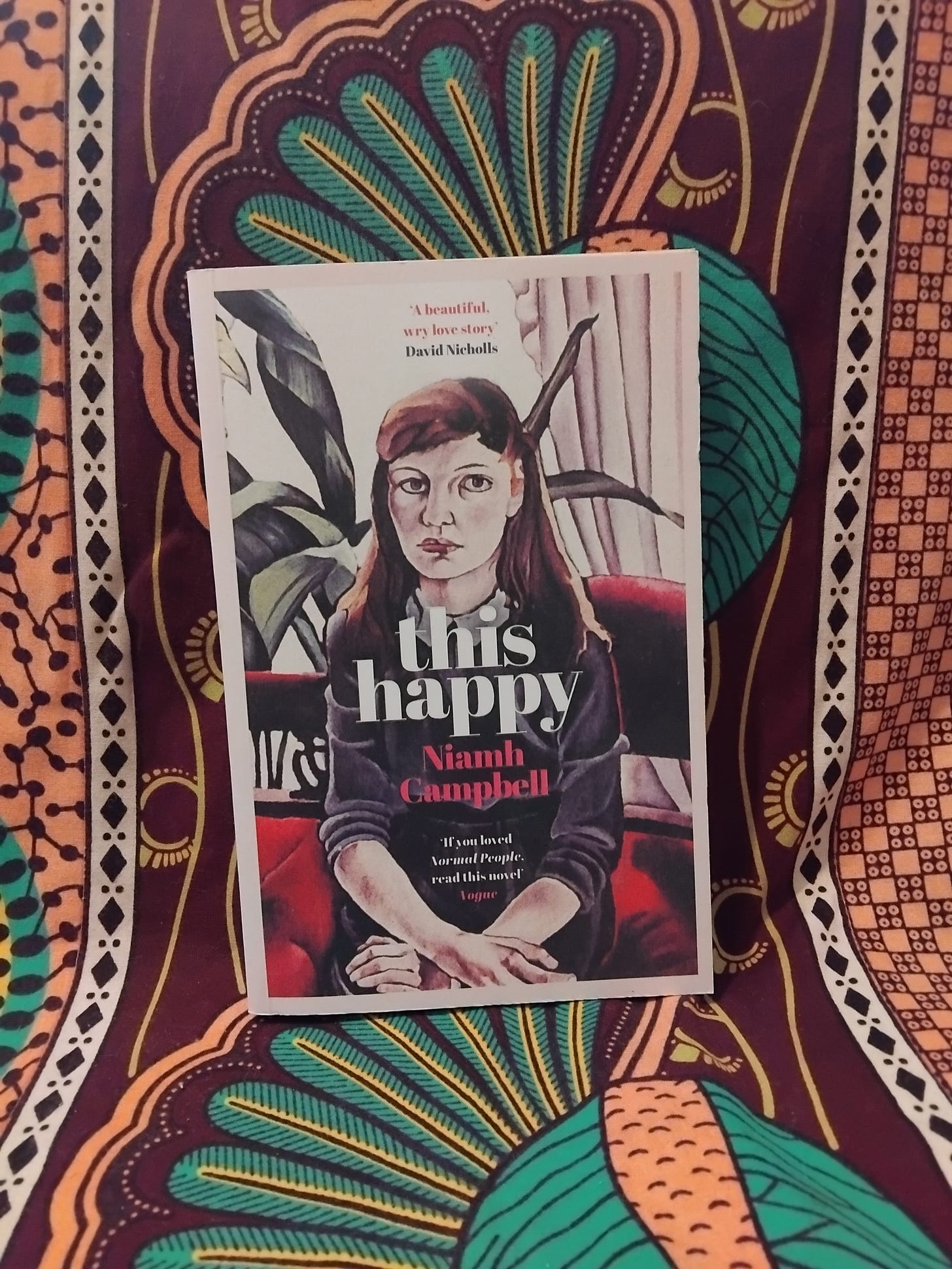

For this edition of Conversations, I chat with Niamh Campbell whose debut novel This Happy was published by Weidenfeld and Nicolson in 2020, and nominated for the An Post Irish Book Awards, the Kerry Group Irish Novel of the Year Award, and the John McGahern Book Prize. Her second novel We Were Young was published in 2022. She lives and works in Dublin.

In 2020 Niamh won the Sunday Times Audible Short Story Award for her story Love Many, and in 2021 she was awarded the Rooney Prize for Irish Literature. Her short work can be found in The LA Review of Books, The Dublin Review, 3:AM Magazine, Banshee, Tangerine, Five Dials, Granta, and gorse. She has been funded by the Arts Council of Ireland and is 2021 Writer in Residence at University College Dublin.

🌳 https://linktr.ee/Niamh_Campbell

📸 https://www.instagram.com/niamh_campbell_xx/

I really want to just start off by saying I really loved This Happy. I read it during the second wave of Covid, and I was just really in awe of just how raw it is and the way that you kind of explore intimacy in such a very beautiful, delicate way. Which makes me want to ask, how do you prepare to write your book?

Thank you for the kind words about the book, it is lovely to hear that you liked it. My experience of it was quite singular: I had finished third level education and was chronically under-employed (this was at the tail end of the economic crash) and fell into a difficult frame of mind. To cope with depression I took up meditation, and some of the clarity I gained from it made me realise I’d always wanted to be a novelist and never really indulged that desire properly. I applied for a grant from the Arts Council of Ireland promised myself that, if I got it, I would quit work and commit one year to writing and selling a novel – this is what happened, and exactly what I did. I lived cheaply, spent a few hours writing each day, and generally floated in a kind of suspended zone of imaginative openness. It was nice.

I wrote the novel as a series of intense vignettes by channelling the voice of the protagonist, Alannah, and letting her ‘say’, feel, desire, disclose, and connive in any way she liked. I was in flow a lot of the time. When it was nearly done I started dealing with an agent, editors, readers, etc., and worked to put a firmer structure on the book ahead of selling it to W&N. I’ve written a second novel since, and am writing a third, but I’ve never done it like that again – open-ended, with total devotion, when young and unencumbered.

Do you write on the go on your phone? Or are you more of an analogue sort of a writer?

I’ve never been analogue, to my shame, but I only ever write on my laptop. I find it hard to keep notes or focus on the go, so it tends to involve me sitting down for 1-3 hours and trying to summon things, or working from a skeleton plan.

I think it could be said that This Happy is plotless. The book is broadly structured around Alannah’s interior thoughts, experiences and memories. Did you decide for the book to be this way?

Yes. I have always suspected plot of being artificial – a plot is something you apply to your life consciously, to make sense of it, but the truth is that much of life is a mysterious confluence of events and interior intensities, and that is the energy I am interested in. This probably reflects a rather Irish obsession with modernism (I do not know why that obsession exists, but if you look at Irish writers, they tend to write in modernist style even now, automatically). It also reflects my lifelong sense that I am, personally, odd or different – I was a sensitive child and felt, early on, that all the adults were lying to me; when I was young I tended to go in search of emotional ‘truths’ and put myself in difficult emotional situations (hence the high, often kind of stupid, emotionality of Alannah in This Happy) and, with my first novel, I wanted to put that affect across, rather than silo things into a plot. These days I have more appreciation for the structure and help plot can give you. But I still don’t trust it.

Who are the writers working now that inspire you?

I have a bank of authors, dead and alive, whom I consider my great influences, but I am also susceptible to finding new writing inspiring too. Most recently, I am learning from George Saunders, Maggie Armstrong, Curtis Garner, and Adam Thirlwell – but it changes all the time.

With writers, actors and playwrights at the forefront, Ireland has held on steadily to a certain amount of soft power over the last few years. Do you think there’s something Ireland is doing right that other cultures might be missing out on?

An interesting question. As it happens, last week I read an old analytical report on Irish design (from the 1970s) which had been commissioned by the then-government to find out why Ireland had such a poor design culture (in terms of textiles, ornamentation, furniture, indigenous fashion, etc.) One of the dismal points made was that, culturally speaking, Ireland was fixated on creative writing and not interested in nurturing any other art form in a meaningful way. This is less true now, but writing is still the most common and most feted form of cultural expression, which is – it must be said – kind of weird.

Personally, I think there are a number of specific reasons for this: [a] postcolonial education system still based on the old British model, and therefore heavily biased in favour of essay writing; [b] writing is cheap and has few overheads, therefore does not require much government funding; [c] our international reputation post Joyce, Beckett and Heaney is assured; this gives people confidence, and [d] people read a lot in Ireland, we have a strong library system, and it’s considered a normal thing to do with your life (as opposed to, say, making sculpture or producing experimental dance, which might make your family stage an intervention).

In an interview a couple of years ago you talked about the cost of living in Dublin. Last year Sally Rooney wrote about the cost of living in Ireland being sky high. What is your experience now?

It continues to be a huge problem, made worse by our housing shortage, which is chronic and apparently unfixable. In my twenties I wrote and lived in shabby houseshares and rode my bike everywhere and made do with sacrificing standards of living for my art; these days I am a married mother with a mortgage, and I work as a lecturer to pay for that. It reduces my scope for writing and I am somewhat haunted by this fact, but I also can’t be doing with boxrooms and scrambled egg for dinner every night anymore. I left Dublin – I live in the southwest now, where it’s cheaper.

Do you think you are in an even more vulnerable position because you’re an artist?

I am privileged to have a good education and be employed. When I was writing, my vulnerability was chosen; I could have gone into full-time work if I wanted, but it meant a lot to me to preserve my freedom. I think the truly vulnerable in Ireland right now are those on low wages, especially people with children, and people suffering with poor mental health. However, writing or any art form definitely makes you less likely to be stable – financial exigencies can kill, or seriously injure, careers. It is also a difficult world to age in. Youth and debut glamour are all fine and well, but one wants to write into one’s unsexy thirties and forties and still be taken seriously.

You’ve also written about the Sally Rooney phenomenon and the “hostility towards the woman writer under 40 as (a) consumable entity”. Where do you think we are now?

This always makes me smile. There was a moment, when I first appeared, when this reductive and sexist and jealous discourse existed, which aimed to undermine women writers by suggesting we were financial products. It’s good old-fashioned misogyny and all we could do was rise above it and keep writing. I love Sally’s work; I know and read a whole cohort of female Irish writers and we are not adversaries but colleagues. And the world has definitely moved on to new things.

In the same essay, you wrote:

“…I write because I want to be seen, and heard, and responded to, just not via the usual channels. I want to talk to you through this machine which also protects me from being answerable; I have found, since the book came out, that my own life and essence now exist in the world as a Rorschach test people interpret for me and give me, in this way, the gift of perspective and connectedness. This mirroring is subtle and nourishing.”

Four years and two books later, how do you find yourself with respect to this want to be seen and heard?

I am smiling at my past stridency again! I have to say, it’s been wonderful; I did not know what to expect when I began publishing fiction, and this sense that your work exists for people in an intimate way – and this is true of my second novel We Were Young even more so than my first – and that people have feelings about it, and you, and reach out to you, this was all amazing to me. It is very fulfilling and interesting. I have gone incognito since my baby was born last year, and now I am writing very slowly, so I feel nervous about the next book and how this experience of being received and interpreted will change or evolve.

At 17 you won an award for your first ever poem Circles, but you didn’t write poetry after that. Cut to some years later, you’d have written two novels, won at least 3 awards between the both of them.

Which form of writing do you veer more towards?

As a teenager I thought I was going to be a poet. Then I went to college, and realised quickly that I was not going to be good enough, as a poet, to cut it – poetry is extremely difficult and a little mystical. I liked the pragmatic, durational, lived-in feel of novels more. I definitely prefer writing long form fiction to short fiction or poetry, though I also write short non-fiction a lot. Novels are roomy and comfortable.

Once your work is published – an essay, a book – how do you perceive it? Are you critical or satisfied with what’s out?

I avoid reading it or thinking about it in detail ever again. This is strange and I am not wholly sure why, but I think it might be to do with my sensitivity and the fact that publishing work leaves you exposed. You give a bit of yourself to people, intimately, even if they don’t realise that. To cope with the exquisite embarrassment this inspires in me, I sort of block the book out. I’ve been in conversation with people over the years and they might say something like, ‘oh you mentioned this in your book’ or whatever, and I have totally forgotten about it. As if someone else wrote the book. I have boundaries, within me, between different parts of myself.

Over the last few years Dublin has morphed into one of the key European tech hubs. There’s lots of jobs, offices coming up, people coming in from different parts of the world. How does that impact your relationship with the city?

The best thing about writing from Dublin is that it’s basically a big village; you can never really get away from your exes, your enemies, gossip, etc. This makes it perfect for novels and soap operas. But this is also the experience of an insider; I have no idea what it’s like to arrive here from Mumbai or California or Berlin and try to get a hold of it. I suspect it’s tricky, but also that there are other communities – we have a large Brazilian population, for example – with their own cliques and insights and versions of the city, and that in the future we’ll start to see more writing and representation from those communities, with a different spin.

I’m definitely interested in the tech element, though. It helped to drive a hipster gentrification of what was, before that, an insular and old-fashioned regional city nobody wanted to live in. I was witness to that and feel both inside and outside that cosmopolitan culture; I also miss it, a little, now that I live in rural Ireland.

While as a UCD Writer in Residence you hosted a series of Conversations with Contemporaries. What was the aim behind that exercise and did the end result satisfy you?

I was writer in residence during lockdown, so everything was remote, and this allowed me to invite people I was interested in to talk about interesting subjects for cheap. I hosted them all from the breakfast bar in the apartment I was renting at the time, which was, in retrospect, surreal. I was hoping for chats about the writing life; about what it’s like to try to capture contemporary life in what is, at base, an old form of expression (the realist novel, though I also invited poets). I found it nerve-wracking and, for that reason, I don’t remember much of it now. After the pandemic I met the man who is now my husband and he discovered, when emptying an inbox or something, that he had purchased an online ticket to one of those events. He has no recollection of attending it either. The lockdown was a strange time.

Has motherhood changed your writing practice?

Oh boy, yes. Having my baby caused a huge rupture in my sense of self and for months and months I felt like ‘a bot’ – like everything I wrote was disassociated, automated, unreal. In retrospect I was quite hard on myself. I feel back in the saddle now, so to speak, and writing more or less the same way I used to write, but with less time and less headspace. I have a shallower grasp of what I am doing, but a deeper and richer supply of emotional, existential, and practical content.

Motherhood involves a lot of responsibility and labour, though, which came as a shock to me, since I had been so unfettered and self-indulgent (and happily so) for years. For instance, last week I cleared three days to write, and then my toddler was sent home from creche with croup, and those three days were simply lost. Having to accept that, go with the flow, step back from ‘productivity mode’, and enjoy simply being there for my daughter is grounding on a lot of levels.

What’s next?

I am writing a novel and I am enjoying it, but it’s progressing slowly and shakily. I think it will take longer than the last two took, but I also hope it will be solid and different from the last two – more hard-won. It is only now that I am sharing parts with my agent and making any kind of plan, so it’s in a tender space.

Read older editions of Conversations here.

If you enjoyed reading this, the next conversation will reach you same time, same place next Friday! Subscribe here & share with the reader types in your lifeeee!