#Scurf189: Conversation with David Hering

The cinephile and bibliophile on literature and film criticism

For the ninth edition of Conversations I interviewed David Hering, a writer based in Liverpool, England. David’s fiction and essays have appeared in The New York Review of Books, The Point, Guernica, The Los Angeles Review of Books, The London Magazine, 3:AM, The Quietus, and others. He is the author of David Foster Wallace: Fiction and Form (Bloomsbury, 2016). In 2019 he was shortlisted for the Fitzcarraldo Editions Novel Prize and in 2020 the Northern Book Prize. He teaches contemporary literature at the University of Liverpool.

👨🏻💻 https://www.davidhering.com/about

Recent essays:

Viewing the Ob-scene: On Jonathan Glazer’s “The Zone of Interest” for The Los Angeles Review of Books

Over the Water Éric Rohmer after Europe for The Point

To kick things off, could you please give a swift intro about your work?

I’m a novelist and short story writer, an essayist and critic, and also an academic, so my writing covers quite a lot of different areas. My criticism and nonfiction is generally about contemporary art and culture, with a particular focus on film and literature.

I read your Point Mag essay “Over the Water: Éric Rohmer after Europe” last year. I too am a Rohmer fan and often find myself turning to his work especially to kill hours of immense boredom. But more often than not, his films send me back into the real world with a sense of ennui, a sense that we’re all broken in ways we don’t fully grasp.

What has your experience with his work been?

I didn’t come to Rohmer until relatively recently. When I was young and dumb, I tended to avoid films with a lack of obvious cinematic style. In the last decade or so I’ve learned to appreciate how style can work more subtly, and Rohmer is a great example of that. I think it’s that with French cinema you tend to come to it via the most self-consciously stylised elements of the New Wave, whereas it took me a while to figure out that my favourite French directors – Bresson, Varda, Rohmer – were operating in a rather different way. In particular, I just fell in love with the way Rohmer uses colour. There’s very little in his films that you could call shocking, and that extends to his use of light and colour; he’ll combine several shades of blue or green, for example, in relation to the different outfits and groupings of his characters as they appear in the frame, and you get a cumulative effect whereby the emotional temperature of the scene is dictated in advance by those colours – you realise subconsciously through that arrangement how the scene is going to play out emotionally before it actually does, which doubles the pleasure of the resolution. I love that.

Over the last few months you completed reading all the seven volumes of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. Is there a specific reason you decided to read these volumes now? What would your, in a LinkedIn-esque way, key takeaways from reading Proust be?

I wanted to read the first volume because Lydia Davis had translated it, and also, if I’m being honest, because I wanted an excuse to start the whole thing but not to feel too intimidated. So if I just had the first volume in mind, I could cut and run after that. And then, of course, you want to keep reading. I know some people really go for the society scenes in Proust, but my favourite stuff is those reveries on minute detail or texture; there’s a whole section in La Prisonnière that I love where the narrator talks about the bar of light that appears under a door at night.

I think Proust is the great writer of sleep, of its degrees, of how it feels to be on the edge of sleep and sinking slowly out of the world, of the degradation or diffusion of language and thought at the threshold of sleep. And it’s one of his most prevalent themes across the whole sequence.

When I think of Proust’s prose my mental association is with a very heavily furnished, dark bedroom, full of curtains and blankets that soften sound.

Do you structure your days based on the writing assignments that you need to get done versus other work?

I’m an academic, so the day is balanced between teaching, admin and writing. My preference is to begin the day by writing, but that’s not always how it works out, so you have to be creative. I’m also a dad, so I need to work around school hours, which does tend to focus the mind.

Do you think films can be considered literature?

No, they’re different forms. But I don’t necessarily think that we need entirely distinct theoretical frameworks for writing about them both. There are certain writers who I come back to – Walter Benjamin, Roland Barthes, Susan Sontag – who are able to think about both visual media and literature in a way that recognises that they’re an expression of a particular culture. It’s important to familiarise yourself separately with theorists of both literature and film, and I do, but the work that influences me tends to sit in that cultural space between forms.

Do you have a writing playlist?

I need silence to write! Always have done.

You tweeted about your favourite films, old and new, from the first half of 2024. How do you curate your watchlist?

I don’t consciously think about it. There are directors whose work I follow and who I’ll make an effort to seek out. I’ll keep up with what’s playing at festivals. And honestly, Twitter is amazing if you follow the right people. Very often I’ll see that someone’s posted about a film I’ve never heard of. I’ve recently got into the work of Takashi Ito, for example, just because someone posted about it. My tweeting about films I’ve watched is, in part, a way of returning the favour. And in a broader sense, it’s just about being in a community where you can say “Have you seen this?” or “I reckon you’d like this”, which is something I really prize. I’m also on pretty much constant text and group chats with friends about film and literature, so a lot of stuff comes through there too.

Do you maintain a Letterboxd account? What is your motive behind it beyond cataloguing your movie watching?

I don’t – in an extremely old-fashioned way I record the stuff I’ve read and watched in my phone’s notes app. That’s the Gen Xer in me coming out. At least it’s not a spreadsheet.

What books and movies have shaped you as a writer?

Too many to mention. Best to say “it’s ongoing”.

Recently? Olga Tokarczuk, Fleur Jaeggy, Clarice Lispector, Kafka, Can Xue, Thomas Mann.

And in cinema? Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Lucrecia Martel, Tsai Ming Liang, Barbara Loden, Hong Sang-soo, Panos Cosmatos, Ryusuke Hamaguchi, Laura Citarella, Aki Kaurismaki.

How do you come up with ideas that you want to write essays on? What happens to the ideas that are not picked up by publications?

Usually I get ideas while experiencing a film or a book or an artwork, and the essay spirals outwards from there. I tend to plan stuff fairly extensively before I write it, so I tend to let it percolate for a while. But on other occasions the idea appears very suddenly. I saw The Zone of Interest at the beginning of the year, and by the time I came out of the screening I knew that I wanted to write about it, and exactly what aspects of it I wanted to write about. In terms of stuff that doesn’t get picked up – if it’s a good idea it’ll be tough enough to withstand a few rejections. If it’s not built to last, it’ll just melt away in the meantime.

We tend to face a lot of rejection as writers, especially freelancers who work on projects as per interest over as per requirement or need. How has your perception, or your relationship to, rejection changed over the years?

When I started writing and pitching seriously, I learned pretty quickly that rejection was 90% of the process. The problem is that rejection is so commonplace that it can be hard to tell whether a piece was rejected because it wasn’t good, or whether it wasn’t the right fit, or whether the publication had already decided on what they wanted. So you go through this stage at the beginning where you can’t get arrested, and you don’t know if what you’re doing is working. And I’m quite impatient by nature, so it can feel as if you’re not making progress. The answer to this, I think, is to talk to other writers – I’m lucky to know a lot of writers at various different stages of their careers, and we help each other. It all comes back to community, I think. No one becomes a writer entirely on their own, as much as it can be a solitary pursuit.

What is your writing, movie watching routine like on any given week?

I write best in the morning, so providing I’m not teaching or in meetings I’ll try to get a few hours in before midday. Movies tend largely to be in the evening, and I’ll usually watch with my wife – we’ve got broadly similar tastes, but if it’s actively viewer-hostile I’ll watch it alone.

Any film directors you’ve recently enjoyed discovering?

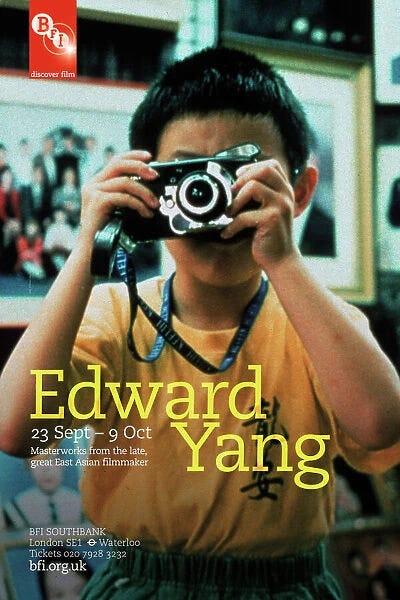

Edward Yang. I’d seen his final film Yi Yi some years back and hadn’t quite connected to it, but rewatched it recently and it was a revelation. So I sought out the rest of his films – he only made seven – and they’re all incredible. A lot of it is very specifically about the hierarchies of Taiwanese society, and I’m probably missing some of the more indirect social commentary, but they’re also timeless in their central dilemmas and tragedies. In recent years, as with Rohmer, I’ve gravitated towards appreciating a mise-en-scene that foregrounds a kind of stillness, that lets the image and scenario play out, that isn’t so antic in its style, and Yang is great for that – he has what I’d call a quiet style, which is an idea I’ve been thinking about a lot recently in relation to cinema.

Are there any essayists (on film especially) working right now whose work you really admire? (This is a selfish question.)

A.V. Marraccini’s book We The Parasites is one of the best works of aesthetic criticism I’ve read in years. Eugenie Brinkema’s work on film is something I admire a lot too. She’s a rare example of a critic whose thesis I don’t really agree with, but whose writing is so good that I enjoy reading her work anyway. She has an essay in her book The Forms of the Affects on the tear on Janet Leigh’s face following her murder in Psycho – well, it might be a tear or it might be a drop of water – and she extrapolates from that in this way that is just dazzling. For film criticism and reviews I tend to read Reverse Shot and Film Comment, as they talk about the films in a way that goes beyond saying whether the film is ‘good’ or not, which strikes me as a fairly redundant criteria for art criticism anyway. One of my hobbyhorses is that mainstream newspaper and online film criticism virtually never talks about the form or technical aspects of the films under review. They talk about the effect but not how the effect’s created. And it’s not like you have to get into focal lengths or film stock or anything like that, you can just talk about the basic building blocks of how the filmmaker works or how a given scene is arranged to give a sense of what the film’s like. But virtually no one does it.

When you're not writing, what do you do?

Family stuff, walking, watching, sleeping.

Are there any upcoming projects you’d like to share?

I’m finishing up a book on ghosts in contemporary culture, which is kind of a work of literary theory and philosophy, and which features a lot of Walter Benjamin. That should be done very soon. Then there’s a new novel percolating, part of which was published last year in The London Magazine. And, perhaps inevitably, I’m also writing a book on cinema. But that’s all I can say right now!

Read older editions of Conversations here

If you enjoyed reading this, the next conversation will reach you same time, same place next Friday! Subscribe here & share with the reader types in your lifeeee!