#Scurf182: Toying with Psychogeography or crying in new places

How writing, being, living shifts in places new, when we always have to carry our old selves aka the itinerant ways of the self

Wherever I go, away from my house (?), my station where I’ve spent an inordinate amount of time just being, I often find myself crumbling immediately at first. The first 2-3 days feel like I am a fish out of water, flung into the concrete of a freshly tarred road and now trying to find my own way through it all. It is emotional, physical, psychological. I am distorted by the vision of the world around, how it makes me feel and where I suddenly have landed almost with a thwack, as if someone forced me to make this travel.

It is after the first couple of days that I find myself, my own self, me, back in my senses. By this time I have settled in the environment around, created a psychological cocoon and possibly also attuned my senses to the place that’s accumulated itself.

This obviously brings me to the term “psychogeography”. The Tate’s website described it as “the effect of a geographical location on the emotions and behaviour of individuals”. It is pretty straightforward, the term refers directly to the physical sense in which a person, a place or even a micro-climate will make us feel and behave differently.

The word, Tate’s website goes on, was invented by the Marxist theorist Guy Debord in 1955 in order to explore this particular feeling. It reminds me immediately of the books of Darran Anderson, Lauren Elkin and Deborah Levy. Their essays, fiction and memoirs carry me immediately to places where I’d love to luxuriate and even gather moss in my own being.

Like a cesspool of one’s own being. A moshpit. A substratum. Flotsam. An atmosphere.

Psychogeography lends itself easily to various readings in several contexts. First of them being in the sometimes inventive, oftentimes boring, and mostly un-charming ways in which we see time, our environment and our physical beings coalesce into one another each time we move. And by moving it doesn’t necessarily have to mean packing up and leaving a place for good, even moving from the bedroom to the home office desk, or the toilet pot to the kitchen sink can cause a change in climates.

The Tate website adds: “Inspired by the French nineteenth century poet and writer Charles Baudelaire’s concept of the flâneur – an urban wanderer – Debord suggested playful and inventive ways of navigating the urban environment in order to examine its architecture and spaces.”

This is immensely interesting to me because these are the primary preoccupations with which I often find myself in confrontation. When in the streets of a new place, walking through obscure every day markets, observing broken pavements, or wandering through the evening bluesy flower bazaars, I find my senses broaden and absorb so many of the tiny, minuscule details around me. The body is gathering more and more data to get accustomed to the (new) milieu.

While in the next moment, when I get to the indoors, surround by the everyday paraphernalia of living like my own un-patterened clothes in a cabin luggage, my meds in a pouch that does not have a fixed place, my walking shoes too muddy, my gadgets too many — there is an unnerving feeling of being out of place. Everything around points to that constantly and disallows me from being able to soak in the new (however momentarily) place.

It is then that I realise that being on the streets, hanging out on the balcony or just moving endlessly on the terrace in these new places gives me an immense sense of freedom not only from the place I was earlier in, but also from the inner workings of my own being. In walking the terrace while listening to Rachel Cusk on a podcast, I am obliviating the everyday around me and immersing my body in a space that has no boundaries. In walking the evening street bazaar, I am allowing the newness of my surroundings to greet me not only through physical appearance but also through hearing, smelling and touching.

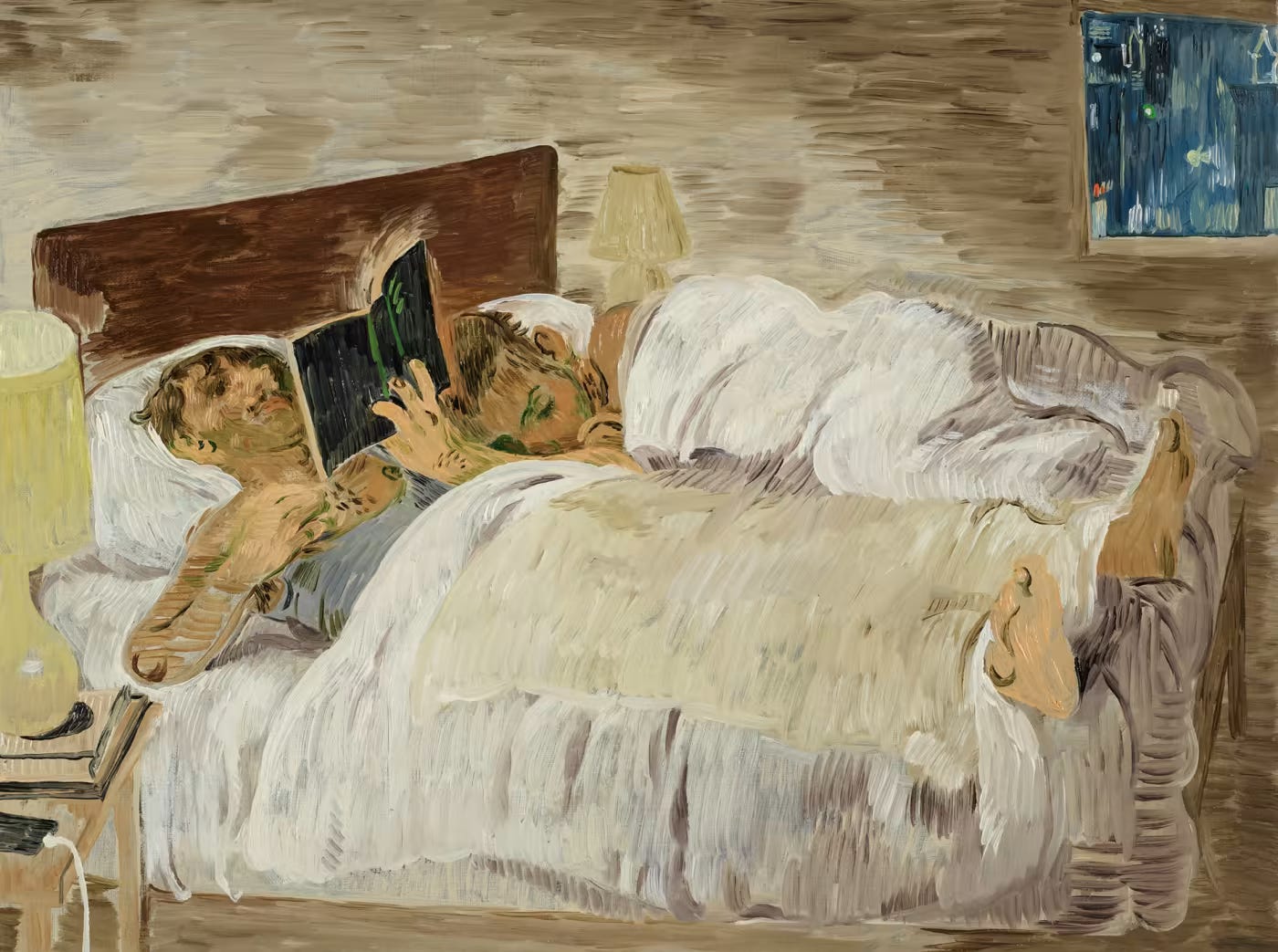

Pakistani artist Salman Toor’s paintings often show moments of fleeting intimacy; a sense of a threshold being crossed. Through his work the artist continues to return to these supposed brief encounters. When asked about these, Toor said: “I grew up in a homophobic culture; I went to an all-boys’ prep school, and I also grew up in a pretty conservative, culturally Muslim family. There was zero visibility of forms of affection in public spaces. So yes, for me to do these paintings is to be on the verge of a threshold.” In painting these spaces whether from memory, or imagination or a confluence of both, Toor is working to alter his sense of the psychogeography. He possibly wants to go back in time and instead of reliving the hurt, he wants to undo those moments and create a new, bulbous, freshly painted memory.

“I was skirting around the more meaningful things in my life, which was the struggle to be out, to make connections between the culture in which I was born and the culture (American) that I have adopted, and the friendships that mean everything to me,” he adds. He states how his paintings were immediately impacted by his adopted homeland which granted him forms of freedom while allowing him to carry within while also continuously redoing the hurt that made up (and came from) his place of birth. “(The work) was just bursting out of me,” he says.

I realise how “détournement,” the reuse of pre-existing artistic elements or media in a new way —a practice of Debord — is on full use here. My dérive from learning and leaning into psychogeography is my self developed process to experience brief stays in a variety of atmospheres. In Bangalore I drift through Whitefield, staying only a few days. I do not scout locations as if on a reccee, I simply strive to find spaces in public where I immediately feel relaxed mentally and physically, places that impact me emotionally.

It so happens that these places are street corners, stripped sidewalks, takeaway kerbside restaurants. None too extraordinary, none out of the world, all too banal, mundane, albeit a bit different to the kind of places I was accustomed to in Delhi. Back in Delhi I often call the whole ecology around me as “the great boil” and coincidentally enough when I traveled to this side of the country last week, I brought with me what I joked with friends the “heatwave vibe”. It ceased to rain, the sun shone hard and bright in Bengaluru as I spent my days waiting in the balcony for the famously inclement weather to turn up. I know when I crawl back to the supposed cocoon that Delhi has become for me, I will find myself once again simmering in the broth of my own being, in the endless humid terrains, in the dryness of the Aravallis, amid the edgelord-shaped humans that are found there.

While walking I mostly stop to take the places in through my bodily, sensory devices but also through the lens of my iPhone. I take in these images mentally, and also make these pictures to allow myself to think of them later. I scour through these images, their visuals reminding me of the way I had perhaps expected the place to be and it actually is. I edit them using some apps, straightening their frames, moulding their mood and texture to suit my definition of those places. I do not share them with anyone, not on any social media, but in seeing them and retaining those visual memories of those places I allow myself to be ruined by a false sense of security. This is my version of the place. That the physical places around me are not as different from my imagination, in fact they are closer to the way I perceived them. In doing this, my reality and my perceived sense of it is both same and also vastly disparate from one another.

Walking out on the streets I am very often highly attuned to the fact that in India we spend entire lives in cities that make a concerted, ongoing effort to smudge over our natural features. I try to use mechanical modes to move over these smears and experience whatever comes closest to the senses as a primal mode of existence. In my writing too, I aim to write the way I walk: both attentive to the varied soils I trod through and curious about the dust, specks, stray animals and palash flowers that adorn the nearest hand-drawn cart. The nether ends of the neighbourhoods are where I find the most amount of replenishment. The verve of the city pulsing through me as I put these words to the page.

Writing this, I realise now that this exercise is essentially a form of reimagining of the places around me. The Tate website states that “psychogeography has its roots in dadaism and surrealism, art movements which explored ways of unleashing the subconscious imagination”. This explains why I immediately thought of the works of Elkin, Anderson and Levy when I first came across the term. I would now also add Rachel Cusk’s work to this genre.

Through their works, these writers take us to physical places, spaces that alter, define or challenge their sense of the self. They are not bound by the spaces they usually stay in, the writers realise. And it is these physical spaces and places, where they find themselves suddenly situated in, that make them think of their own emotions, behaviours, patterns in different ways.

Elkin’s writing is quite literally about cities, walking through them, and discovering how associated history alters the way we move through them in any moment. Levy takes in the moods of her marriage, divorce and eventual life circumstances through the shapeshifting candour and nature of the spaces she finds herself in. These are a family home, a rented apartment, a writing shed, somewhere in Paris on a writing retreat, in parties. The spaces constantly define her place in life, changing her handle on the life, writing, the works.

Anderson’s work also directly corroborates with the violence of physical spaces, how they can so easily be forgotten and yet remain deeply rooted in some of us. He takes us to Derry walking us through his remembrances of the Japanese room in his parent’s house, the shenanigans of his childhood friends that would often alter the neighbourhood into a place of play and immediately a place of imminent danger, a casket of music his father used to listen to. These places often form microclimates around us, either literally in a way we can touch and feel them or through their extended form, something more intangible. The memories an incense stick might evoke, the time of the day when someone lights that incense, the way someone aligns their shoes.

Spaces guide, corrode and also emulsify our senses, all the while without much of our immediate knowledge, propelling us to think of it as a disturbance or a change in place that leads to a shift in mood or cadences.

The painter Richard Diebenkorn once described his process: “I don't go into the studio with the idea of 'saying' something. What I do is face the blank canvas and put a few arbitrary marks on it that start me on some sort of dialogue.”

This put a finger to how a lot of writing for these (and other) writers comes from being displaced. Cusk’s Outline Trilogy captures something similar. The frictions in her life give rise to these stories, their infraordinariness and hence her sense of being flung out of place.

I wonder then what the meaning of this writing is, the writing that comes from being thrown into a non-oblivion like this and yet that speaks itself so clearly to me. It is: I am here.

Writing these substacks over the last few years has unexpectedly brought me closer to other readers, writers and walkers. If reading this dredges up resonant memories or stirs up a wonderful pot of emotions within you, I’d love if you left a comment, or shared this with a reader friend!

Anandi is a writer based in Delhi.

Related essays: