#Scurf183: Conversation with Anna

On academic writing, Agnes Callard's conservatism and Charlie Kauffman's movies

For this edition of Conversations, I speak with Anna Hart, a 24-year-old philosophy student from England. Anna is interested most of all in aesthetics and ethics—for now, at least. Her MA was on the feeling of being disappointed by artworks. She wants to believe that philosophy can help us figure out how to live; she just hasn't figured out how yet.

You might know Anna from some of her viral tweets around reading Proust, navigating philosophy and such things. She’s also writes routine dispatches on her substack on the subject of philosophy, her readings and observations.

Could you share a little bit about your background and how you came into writing about philosophy? Are you currently studying philosophy?

I’m currently in between my Masters and Doctoral degrees; I’ll be starting the PhD in October. My first encounters with philosophy were as a teenager: I had religion classes at school, and through those I was introduced to ideas about morality, arguments for the existence of God, and so on. My teachers could tell I was becoming interested in it, and they encouraged me to read more than what was assigned to us in class. This was exciting to me, though it became more and more of a labyrinth. I think the first years of studying philosophy can take the form of an accumulation of names and labels, without much wisdom for what goes where. In these years our beliefs are often determined by whatever it is we read last. Probably the book that was most consequential for me at this point was Augustine’s Confessions. His self-consciousness and unease in himself resonated with me. The Confessions show Augustine turning to philosophy when his life itself has become a question for him; I think it converted me towards this conception of philosophising.

In one of your earlier Substacks you say, “Writing philosophy is equally nauseating: I have to artificially put my thinking on hold in order to catch it and depict it in a still form, in pixels or in ink.” Can you expand a bit about your practice of writing philosophy? Would you say that writing is an indelible part of philosophy?

Writing can be a way of talking to yourself. I don’t think that our thoughts, feelings, or beliefs are very clear to us at all, and writing is a way of making them a little clearer. In the sentence you’ve quoted, I guess I’m trying to say that what is difficult in writing is the attempt to transform thinking—which is fast, loose, sometimes incoherent—into something as still as a sentence. The pressure of this is particularly strong with philosophy, where to some extent there is an expectation to develop your own ‘positions’, doctrines, on things—as if you had always had these views, and needed only to get them into words. I appreciate writers like Montaigne and Walt Whitman for being more comfortable with contradicting themselves.

Would you say that pop culture has helped bridge the gap between what was once the domain of doctorate holders, the academia and mainstream, more common people? Also, is that necessarily a good thing?

I don’t know. I suppose it depends on how broad your idea of ‘pop culture’ is. I think a lot of philosophical writing in non-academic publications (like the Boston Review, London Review of Books, The Point magazine, etc.) is very good; I regularly find it way more engaging than academic writing. I think it’s common for people to suggest that a big divide between academic and non-academic thinking is caused by academics writing wilfully obtusely, but I don’t think this is true. Academic writing is boring and characterless far more than it is deliberately obscure. I think the bigger problem is the self-conception of academics (in the humanities, at least—or at the very least in philosophy) as specialised professionals. The professionalisation of philosophy implicitly encourages academic philosophers to think of their work on, say, ethics, as categorically different to what anyone else would ever think about when they think about ethics. But I think this is a mistake, and I respect the academics who make an effort to appeal to a wider audience.

I enjoy reading the occasional Agnes Callard essay in the New Yorker. I feel they serve as meditations on the ideological, political, and public dimensions of the human mind. What do you think about her work?

I think some of Agnes Callard’s writing is interesting, and I appreciate how often she orients her work towards a non-academic audience. At the same time, I think we should ask why a philosopher who is seemingly so committed to taking philosophy out of academia and into the wider world should be so reserved when it comes to the politics of the wider world. If I am remembering correctly, she has often chosen not to support her striking colleagues and has not said anything in support (or anything at all) about the ongoing university encampments in support of Palestine, one of which is at UChicago where she teaches. What good is a professor of ethics if she cannot manage these things? (This is a genuine question.)

In a talk last year Callard argued that the ‘politicisation’ of philosophical issues limits free speech and inhibits the wonder that (according to Plato and Aristotle) philosophy is born out of. I disagree; I think that, at least in some cases, a fear of issues becoming politicised expresses a fear of those issues becoming more than just abstract, intellectual affairs.

Who are your influences in the field of philosophy?

There is Augustine, as I mentioned a minute ago. Another influence, and another of the philosophers I first became interested in at school, is Wittgenstein. He first appealed to me because of how interesting his life was and how emotionally complex he seemed to be. (As a teenager I watched Derek Jarman’s biopic of him, and it inspired me but at the same time gave me an anxious feeling that Wittgenstein had finished philosophy, and there was nothing left for me to be interested in. But Wittgenstein himself says that all he is destroying is ‘houses of cards’; he doesn’t mean to get rid of what is interesting, but change our minds about what is interesting.) In the past couple of years I have become increasingly influenced by Stanley Cavell and Cora Diamond’s therapeutic interpretations of Wittgenstein, and also by Iris Murdoch, who in my view approaches philosophy with the same realistic spirit with which a novelist approaches the world.

Would you consider your substack as academic writing? What would you say is your relationship with nonacademic writing? How did you arrive at the idea of writing a substack about philosophy? Did you feel there was a gap in this area?

While writing my MA thesis, I would start to take notes of thoughts I was having which seemed philosophical but which didn’t seem to have a home in my thesis. There were a lot of thoughts like this, because at the time my philosophical temperament was undergoing some kind of transformation or conversion. (This was largely due to a class I took on Wittgenstein, and because of what I was reading for my MA on the topic of aesthetics.) When I had written a short essay that seemed like a kind of ‘mission statement’ of how I was coming to think about philosophy, I decided to put it online in the hope that other people might be interested in it. If I look back on the first few things I wrote on Substack, I see them a bit like breadcrumbs on a trail towards a certain idea of philosophical writing. I see the things I’ve written since the summer of last year, starting with the thing about insects, as the result of my going down this trail. They might not look like philosophical writings on the surface, but I think (I hope) there is something philosophical illuminating them.

Are there any philosophy substacks you’d recommend?

My favourite substack is Elif Batuman’s! She is a writer and a novelist, not a philosopher per se, but I find a lot of philosophical reflection in the way she writes about life.

I’ve never formally studied philosophy, but it’s through movies like Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind, Lost in Translation and Waking Life that I came closer to some kind of mapping of what it could be. Would you have any such movies in mind?

Yes! You mention Eternal Sunshine, and I’d say that nearly all of Charlie Kaufman’s films—particularly Synecdoche, New York (2008)—have felt philosophically stimulating to me. I don’t think philosophy has to belong to any kind of formal study; it is something that can take place in academic or non-academic writing, in novels, in films, or theatre, or anything else. I tend to be most inspired by films which are not overt and explicit about the philosophical thinking going on in them, but which present stories and lives which prompt as much thought from us as our real stories and real lives. In this way I think fiction can be an exercise of our capacity to know someone. Noah Baumbach, Ingmar Bergman, Lynne Ramsay, and Kenneth Lonergan are some of my favourite examples of filmmakers like this.

For those coming to philosophy fresh, could you share a beginner’s reading list?

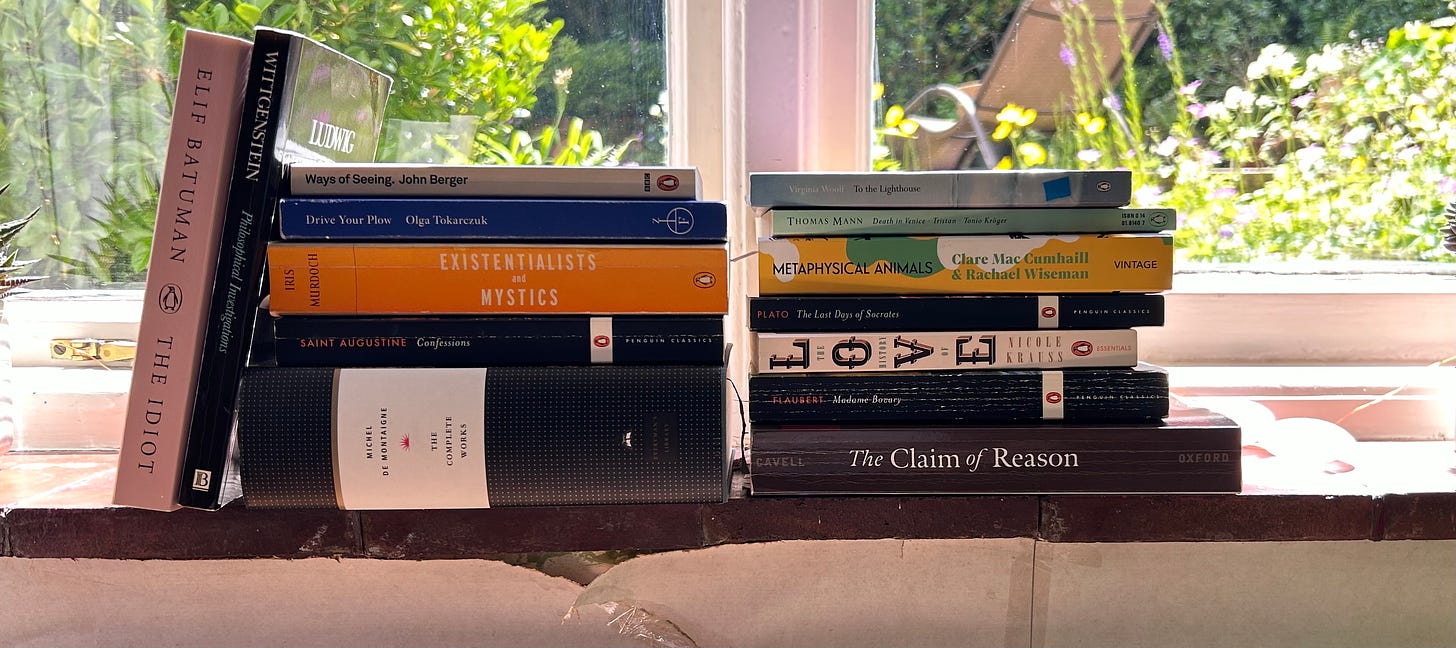

Have a look at Augustine’s Confessions, John Berger’s Ways of Seeing, Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex, or Plato’s Phaedo and read any of them that sound interesting to you. I think the best thing to do is just follow your heart. Don’t get too anxious about getting an overview of the whole history of philosophy, or about misunderstanding something, or about reading the ‘wrong’ thing. If you just keep going, these things tend to sort themselves out.

Any classical and contemporary philosophical novels (novelists) you’d recommend?

Contemporary: Nicole Krauss’s The History of Love; Olga Tokarczuk’s Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead; Ben Lerner’s Leaving the Atocha Station.

Classic: Virginia Woolf’s To The Lighthouse; Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary; Thomas Mann’s Tonio Kröger, which is a novella.

I think all good novels are philosophical; the greatest novels are something that philosophy should live up to, and not vice versa.

What are you reading currently?

I’m about to start Metaphysical Animals, which is a recent book about four women philosophers in wartime Oxford: Iris Murdoch, Philippa Foot, Mary Midgley, and Elizabeth Anscombe.

You can read the earlier conversations in this series here!