#Scurf140: Does the visual memory hold?

Some thoughts on the urge to photograph, and what gets lost in translation

When I thought of writing this dispatch, I found myself scrolling through recent photos on my cloud account. Scouring through these photos I realised how almost all these photographs are first and foremost memories, notes, bookmarks.

You want to read something? You take a screenshot. You want to remember someone’s phone number? You write it on a piece of paper and then take a photo of it. You’re in a moment and want to preserve it in the recesses of mind for a longer duration? Snap out the phone and click a photograph.

More than anything else, these photographs in my gallery and cloud have taken on the form of something that is more than its immediate self. They have become what once used to be my notes, my drafts, my post-its, my scribbles. Less paper used up that way, but am I able to remember all these accumulated emotions?

One after the other, these are things that don’t have my immediate, full attention, but somehow I reckon they’re important in one way or the other. Hence the visual screenlocked saved versions of them. In their abundance they become meaningless acquisitions, just like many things in my house. They were bought with a purpose but soon lost their sheen. I lick my wounds, my wounds that are now in the shape of these digital escarpments where I jot down too much to get back to.

Like lipstick stains on a silk blouse after a night of heavy indulgence, these screenshots and photographs weigh me down, burdening me with the memory of all the things I had set my mental self up for and failed to even recall. There’s glory too, somewhere in that failure. These wounds frolicking around, cause me to feel embarrassed of my over ambitious self. A kind of ferociousness that I hardly see in anyone else around.

Is history deaf there, across the oceans?

Agha Shahid Ali

Perhaps there is also a sense of loss that resides at the heart of these visual accumulations. A loss of the immediacy of joy that occurs when one actually encounters these missives in real life. The joy of coming across a passage so poetic it bowls you over. The spectacular beauty of a bunch of marigolds in your neighbourhood garden. The surprise of running into a cat inside a handloom store. These things are just as, if not more, beautiful in their real time occurrence. Why then is the mind motivated as a knee-jerk reaction to hold up the camera and just shoot a snap?

It is maybe because I didn’t have too many of these joys awhile ago? Or maybe I got wired to take note of them only in the last decade? Perhaps because I have people in my life with whom I could share these? Maybe also because there’s an uncertainty in this act of noticing. It might be here now, but in another moment in time it be just a blip in eternity.

I don’t fully comprehend many things on a routine basis, but most of all what I feel the most weak in the knees kind of powerlessness for is the visual medium and its hold over my senses. Perhaps it is also a childhood thing. Accustomed to watching Hindi movies like Mother India, Ganga Jamuna and Mughal-e-Azam on a regular basis, perhaps the visual mode came to rule my imagination. And that put a kind of a premium on what I find to be the most attractive pieces of work to me.

It is like how the evening air these days is always a cross between noxious greyness and the dullness of winter’s passing. These both airy signposts of my childhood, echoing off from the vast horizon like a forgotten croon of a thumri about a lover long lost.

What started off as gatherings, points to note and remember, has perhaps now morphed into a graveyard that is in a regressing sadness. A slow corrosion snaking up the corridors of the gallery. Like a long train journey from Kanpur to Kanyakumari. I took that once, it took a little less than 48 hours, and however spent I was at the end of it, seeing the last station at the southernmost tip of India felt like an achievement unto its own. I was ready then to go back already, but there was so much more to the place. The temples, the houses, the food, the beaches, the books.

Perhaps now I’ll try looking past these screenshots of amazing times. Now I’ll go into the mind’s eye, as Sophie says in Aftersun, I’ll try “taking a picture from my mind’s camera”. Maybe it’ll be a little more glorious then.

Till then here’s a screenshot of a string of tweets from a moment I lived in so beautifully, I only have the memory of it in this form. Embarrassed at this outburst so early in the day, I remember deleting some or all of these tweets. Nothing I felt could’ve done justice to the moment I was witnessing. No photo, no tweet, no drafts.

I was wrong, the photo I took from the tarmac does speak to that silence.

Some Things I Liked Recently:

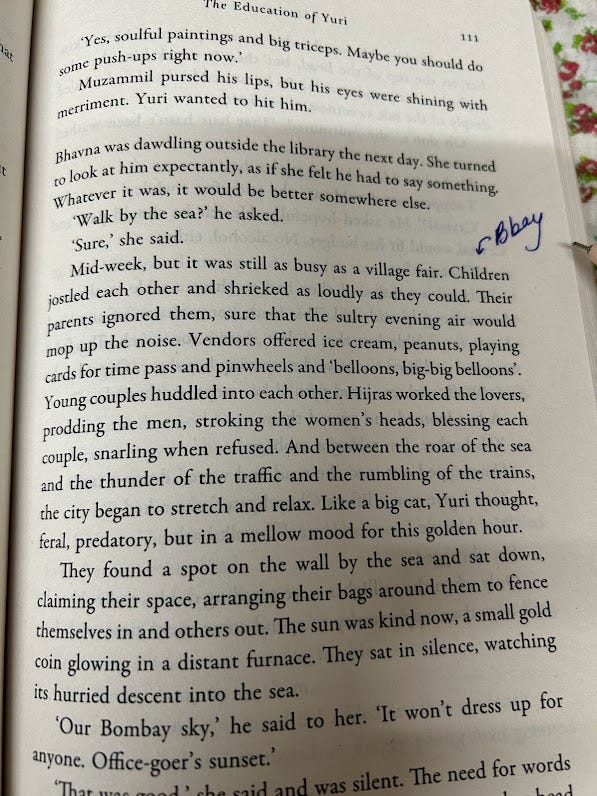

I re read Jerry Pinto’s The Education of Yuri which is to say I re read my favourite, all smiles story of Yuri and his boisterous (in his head) youth. Here is one of my favourite paras from it:

This review of Marguerite Duras’s The Easy Life by Apoorva Tadepalli had me craving more of both their writing. Love this part:

The narrator of any story is necessarily a stranger, observing things (or nothings) from the outside. But a narrator needs to be in the story as well, or at least alive in their own world. Francine’s state of aliveness tests the literary boundaries of this disengagement.

I’ve been basking in the love that Shaunak Sen’s All That Breathes has garnered, more recently with its Oscar nomination! It’s a happiness of knowing that an earnest hard work can really take a life of its own. Read this interview of Sen from 2022.

I want audiences to walk out with the film and look up at the skies. I want them to be enchanted by the skies, even when it’s the noxious gray skies of Delhi.

Lastly, this very detailed interview of Aftersun (2022) director Charollette Wells where she talks about sifting through memory and dealing in its unreality in the movie.

What I loved about the miniDV, when I introduced it, was that it gave a very direct, literal point of view tool from one character to another, and it also offered the opportunity for playback within the film. Calum, for example, could see through her eyes, her perception of him. There’s that scene where she shoots him with his arm hanging out of the shower, because it’s broken and he can’t get it wet. And she’s goofing around and saying, “This is my wonderful, one-armed father.” He watches it back and takes solace in that in one scene, then finds it too difficult to watch in another. It was this fascinating, complicating tool.

Subscribe to Scurf

Thanks for reading. This is a public essay on Scurf. If you enjoyed this, and/or you’d like access to the coming soon, weekly subscriber-only essays and discussion threads, maybe consider subscribing.