Eyes on the street

#Scurf225: Suburban walks in a new city, making meaning, connection, and time

Personally, I started walking to travel, to map and to understand places old, new and familiar around me. I walked with my mother, alone to school, to tuition, to friend’s places, with friends, with my brother, with boyfriends, with lovers. So when last year I found myself in a new country reading a new dialect of winter, walking after dark became my way of finding more about this place. During the stretched out winter in Sweden, evenings descend as early as 3.30pm, giving ample time for walking enthusiasts like me to loiter, linger and take in the sights around the neighborhood one window at a time. To make up for lack of exercise, and also to mark my first Nordic winter, I undertook long walks in my neighborhood.

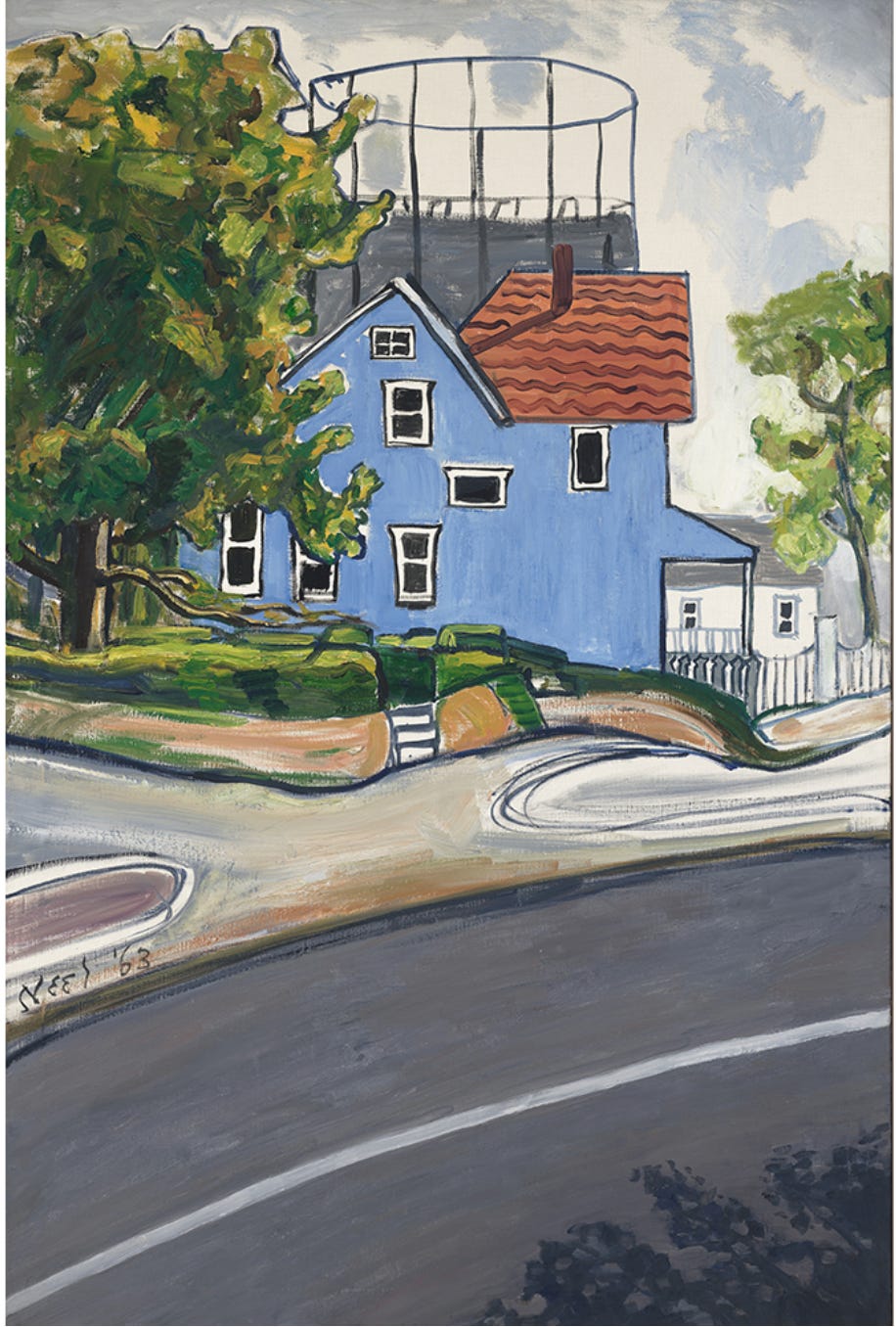

This closely mirrored the way in which I often find myself searching online for Alice Neel’s paintings and lingering on pages, zooming in and out of frames, taking in the views, calibrating, understanding, sometimes not understanding. As a person who spends long stretches of time by herself, in a lot of ways, watching these paintings has been a formative experience for me to enjoy the company of humanity. Neel is known for her humanly, moving, spreadout, voluble portraits of people she knew closely as friends or family, people she had worked with, people who were her neighbours and were former lovers. There’s an expansiveness to these portraits as they embody not only these people, but also their time, their physical belongings, their milieu. In capturing them down to their minutiae, Neel made them look like fuller, more humane versions of themselves. And that’s why I would often return to her paintings. To find a vocabulary to getting to know and understand people better. How else do you get to know a people — you take walks in their cities. So here I was, ambling through these glamorous, rapturous, often deserted by-lanes of Gothenburg, attempting to understand them.

I walked as a way to grasp the realities of movement, perception, and safety. I explored how these new spaces could shape my experiences, and how the act of moving through the city itself becomes a statement of presence. Now, our pocket of Gothenburg cannot be called dense, it’s quite the opposite in fact. There are spread out villas with gardens, that are almost all single-storied and usually have huge windows overlooking the street. The people who live in them, when they’re not living in them are usually cozied up and decked every so chic in their Scandi, deep, gorgeous aesthetic and ensconced away to other places inside their big, beautiful cars. Very rarely I’d find an angry teenager with large apple headphones stomping about lone. Or an old couple taking in the sun, holding each other’s hands or a moving company shifting luggage in or out from a villa. Surprisingly enough, these tight blocks also make walking alone, walking dogs, running, during pitch dark evenings very conducive.

I was not looking for anything specific during these walks, just to distract myself, or listen to that episode of Talk Easy with Hilton Als for a second time. One of my favourite places in this neighborhood is a short stretch of a forest preserved in the middle of the city through with a pond, some mallard ducks and a cacophony of suspicious deers. During winters the pond would freeze, creating an almost ethereal, mystical visage. I spent many an afternoons milling about the hilltop in that forest, trying to see through the cutting silence that envelops the city during winters. In her short story Stone Boy with Dolphin Sylvia Plath fictionalises her own plight from a winter with her husband Ted Hughes, writing:

…she begged, wordless, of the orange bonfire-glow of the town showing faint over the bare treetops, and of the distant jewel-pricks of the stars: let something happen. Let something happen. Something terrible, something bloody. Something to end this endless flaking snowdrift of airmail letters, of blank pages turning in library books. How we go waste, how we go squandering ourselves on air. Let me walk into Phèdre and put on that red cloak of doom. Let me leave my mark.

In lingering, loitering, hovering over the city during winters I felt like Plath’s protagonist here. I felt like I had to make something happen to move me. To move the systems. To call it winter depression would be a misnomer because such distress can happen to anyone at any time of the year or day. And hence, I took up walking to show myself the ways of the world in this part of the world. As I passed by these houses, vignette after vignette of others’ lives revealed themselves to me. After a few days, I began to look forward to these strolls, associating with them the warmth of other people’s lives, the literal glow of their literal inner lives as seen through their windows. I leaned into these saunters to take in the full panoply of life in Gothenburg and after the first two winter months, I had my solitary time chalked out. Come evening and I would venture out indulging in this fortuitous dérive. It became my exercise, my obsession, my distraction, my meditation.

Feeling the thrill of effortless momentum, it did occur to me that this exercise could come across as voyeuristic, even intrusive, but I made petty, pathetic, self-soothing explanations like I was only indulging in an element of healthy anthropological curiosity. That I was reaching for vicarious company. That perhaps I was searching within those pockets of brightness, far away from the duskier recesses of the winter all around (to subvert Woolf’s metaphors). Face in the streetlight, winter cap on, I plodded on, maintaining a steady pace, stealing fervid glimpses, making copious mental notes. This was similar to how I had spent copious hours online staring at Neel’s people instead of actually going out there and accepting invitations to parties and get togethers. From the cossetted confines of my kitchen table and tiny laptop screen, life felt more accurate.

Physically, I was in a new place, experiencing a novel winter, finding my feet in a new culture and amid all this naiveté, a peek through these windows, tramping anonymously elicited a sense of belonging, making me feel less alone. Stranger things have made me feel less alone, and yet here we are. After seven winters of similar walks in Delhi, I was turning corners through the winding lanes of Gothenburg. These walks were all I had in a way. Walking became writing. Without a paper to pen, here I was on these streets, exhorting myself in the journal of my life to observe (write) the things of the would without any glazing. It helped that I was away from social media, unencumbered from the daily nagging requirements of showing up there. In soaking in that vicarious form of living, I made myself believe, perhaps rather schizophrenically, that by merely getting a glance into their lives, I was one of them. Isn’t that also how we behave and believe and become possessed with the illicit lives of others via IG stories? Same difference, bro!

A stately Turkish cat seated at the corner window of one house; a dinner table with the best of candles and decked up faces; a father-daughter duo engaged in a deep game of scrabble; a porcelain dog statue at someone's stoop; the visage of a dimly-lit empty living room; salad bowls; carpets; bookshelves; globes; paintings. These glimpses didn’t make me imagine similar material possessions for myself, or go into endless reveries about the lives of these rich, sophisticates. They simply made me feel less alone, as I stood on the outside, merely trying to look in. This mirrored my tendencies with Neel’s paintings.

Now, Neel is known for her dogged character studies, her uncanny ability to capture intricate moods, patterns even. Her paintings often highlight and amplify a specific quality of her subject, making the portrait stand out while also memorable. In doing so her paintings become an quality above the aesthetic — something ethereal, singular yet also universal. It sticks to you. Often I find myself staring deeply, longingly and squarely at her portraits, thinking of what she has stripped away to carve this person out on the canvas. And that mirrors what I was searching for in these walks — how this house stands out from the one before, or this street’s design better the one after this. Even though I was only observing the surface of the variegated lives around me, I felt a stamp of approval from within. Things seemed to be clicking in.

Another literary adventure Virginia Woolf’s seminal essay Street Haunting springs to mind. Woolf’s protagonist in the essay is bored and distressed at the sight of familiar objects all around in the house. She ventures out to join the “republican army of anonymous trampers” who walk the streets of London, escaping her boredom and giving herself the made up excuse to buy a pencil. Similarly, distressed by the looming coldness, the endless winter darkness, I would venture out, alone to buy that proverbial pencil. To Woolf’s dusky, peopled London streets, I had my own bare, beautiful, stark Gothenburg boulevards. She described those lanes of the home of the Big Ben as “islands of light, and its long groves of darkness”. And here I was, scouring the corners for that purring, roaming cat, and running into old couples, hand-in-hand walking their daily exercise quotas.

Taking the walk back during those days, I’d be slightly jubilant at the prospect of having an evening Fika (Swedish coffee break) by myself. A simple coffee at a favourite cafe with a dessert, usually a Kanelbulle (cinnamon roll) would be a prospect inviting enough. A short tram ride and I find myself at the cafe, usually scrambling to get a table for myself, surrounded by other busy patrons. Soon, I’d nestle in with my cappuccino, fire up the books app on the phone or just sit back and listen to the cafe’s playlist.

I didn’t take any photos during these winter ambles, and while sitting in the cafe, I’d use that time to recollect the sights, committing them to memory by writing down something strange or mundane. Making my own wordy portraits of these hours. Now, in the thick of summer as I scroll past those entries on my notes app, I realise that through all those walks I still carry within me those momentary little paintings that formed on window panes of strangers’ houses. In the midst of an growing summer, here I was, read notes from my former flaneur self. To invert Camus famous quote: “In the midst of summer, I found there was within me an invincible winter.”

A reading list on walking in cities:

As a woman interested in the socioeconomic, political and geographical make of our cities, I have actively sought out books that lend more insight on these aspects of our cities. Along these lines I’m sharing here some books that highlight walking as a tool for observing, and personal reflection. Through various formats (novel, essays, commentary) these writers present a composite of how sensory, liberating and often confusing walking can be. As our lives continue to get more digitally inclined, this reading list will push the readers to read a book and tramp on grass:

Lauren Elkin's Flaneuse: Flaneuse focuses on the act of walking as a means of female exploration and liberation. Elkin reclaims the concept of the "flâneur" for women, underlining how "flâneuses" navigate and experience cities. Here, walking becomes a tool for claiming space, observing society, and asserting independence. I wrote about online flaneusing during covid for Ploughshares.

Leslie Kern's Feminist City: Kern examines how urban design often ignores the realities of women's daily lives, where walking can be fraught with safety concerns and accessibility issues. She critiques the ways in which cities are not "walkable" for everyone, particularly women and marginalized groups, due to factors like street lighting, harassment, and the layout of public spaces. Here walking is viewed through the lens of safety and equality.

Jane Jacobs' The Birth and Death of American Cities: Jacobs emphasizes the importance of pedestrian-friendly urban environments. She advocates for street-level activity, mixed-use neighborhoods, and "eyes on the street" as crucial elements for creating vibrant and safe cities. Walking is seen as essential for fostering community and promoting urban vitality, and therefore this book becomes an essential for this list. I wrote about finding a slice of Jacobian city life in the Delhi of lockdowns for Popula.

Italo Calvino’s Invisible Cities: While not focused on the physical act of walking, Calvino uses the descriptions of imagined cities to evoke a sense of wandering and exploration. The reader "walks" through these fantastical urban spaces through Marco Polo's narratives, engaging with the city on an imaginative as well as philosophical tangent.

Vivian Gornick's The Odd Woman and the City: Gornick uses walking as a way to connect with the city's cadences and also observe its inhabitants. In doing so, her walks become a form of self-discovery, allowing her to explore her own identity in relation to the urban environment.

Taran Khan's Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul: Defying warnings, Khan maps Kabul's streets, using her footsteps to map the city's hidden narratives. Each walk becomes a journey through layers of history and resilience, revealing a city beyond conflict. Her walks uncover intimate stories, challenging restrictive norms and reclaiming space. I reviewed the book for the Chicago Review of Book here.