Conversation with Darran Anderson (II)

#Scurf200: On coming of age on the internet, preserving some precious moments in the personal space and Bachelard.

This is the second part of the conversation with the writer Darran Anderson. Read part one here.

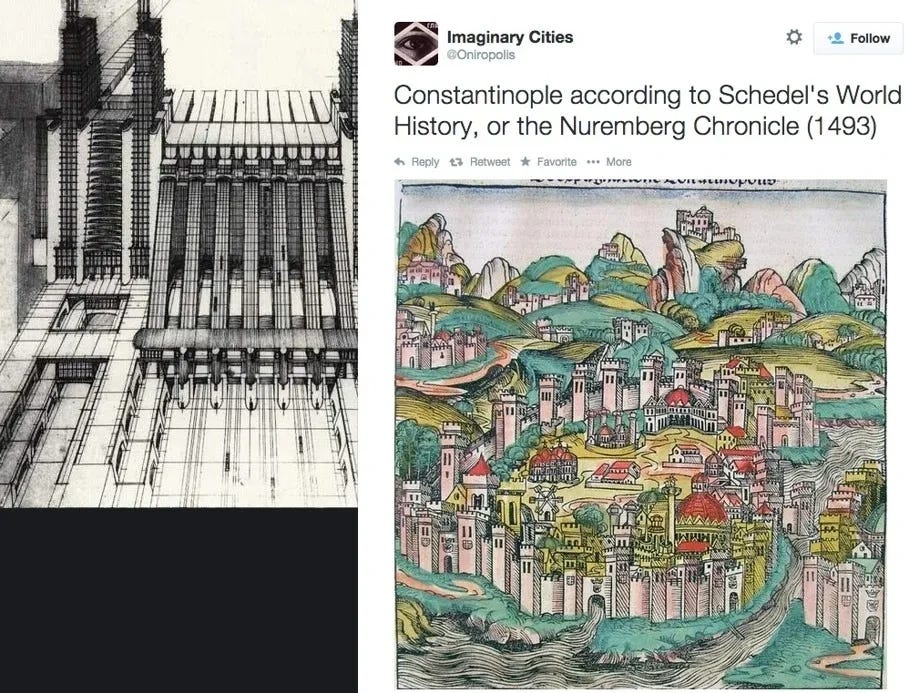

Anderson is an essayist and memoirist writing at the intersections of culture, politics, urbanism, and technology, has been recognised for his debut Imaginary Cities: A Tour of Dream Cities, Nightmare Cities, and Everywhere in Between (2015), a hugely ambitious analysis of real and imagined cities throughout history, and Inventory (2020), his searing memoir about growing up in poverty in Derry. Anderson was awarded the Windham-Campbell Prize in 2023.

Could you talk a little bit about how Gaston Bachelard’s ‘The Poetics of Space’ inspires you?

My favourite books are always basically maps that send you out in different directions – Lipstick Traces by Greil Marcus, The Wanderer and His Charts by Kenneth White, Modern Times, Modern Places by Peter Conrad, Ralph Waldo Emerson’s Journals and Montaigne’s Essays, Religion and the Decline of Magic by Keith Thomas, Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project and his Berlin Childhood Around 1900, encyclopaedias like Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, some recent books like Olga Tokarczuk’s Flights, Rob Doyle’s Autobibliography, Merve Emre’s Paraliterary, Anahid Nersessian’s Utopia, Limited: Romanticism and Adjustment. A book I’m truly obsessed with, my desert island book, is The Road to Xanadu - A Study in the Ways of the Imagination by John Livingston Lowes, which is a study of Coleridge’s notebooks and all the crazed ideas the poet never followed up, something I’ve tried to mimic in an essay for the forthcoming Winter Papers on my own personal library of lost books.

The Poetics of Space is one of those maps. It sends you places, physically and metaphysically, that you never thought you’d visit. And when you get there, you see the world differently. I think in a way, it helps us to revive memories we forgot we possess – the childhood perspective of interiors where rooms were magical and sinister and epic repositories of memory, imagination and stories. It’s had an immense influence on my work, and I see it in other books I respect like Juhani Pallasmaa’s The Eyes of the Skin – Architecture and the Senses. Every time I work with architects, I feel Bachelard there, behind my shoulder, this bearded shade insisting that buildings have souls and somehow, impossibly, he is never wrong. What blind good fortune to have chanced on such a book and path.

Any recent books or movies that you’d like to recommend?

I had the pleasure of watching Celluloid Underground recently in one of my favourite places, Close-Up Cinema just off Brick Lane in the East End of London (thanks to Juliet Jacques for originally taking me there). The director Ehsan Khoshbakht was there and spoke and I just have such admiration for his work in saving film from neglect and wilful destruction. The documentary follows the story of Ahmad Jorghanian, who was an honourable and eccentric collector of film in Iran and was persecuted for his activities. We live in highly censorious times from all directions and, if writers and artists have any calling, I believe very passionately it’s our job to agitate for freedom of expression, against puritans, neurotics and tyrants who seem determined to erase parts of our collective cultural memory. I highly recommend checking the film out and supporting work like Ehsan’s. Nobility is rare in this world, and we can’t afford to squander it.

In terms of recent books, there are so many. Corey Fah Does Social Mobility by Isabel Waidner. The Ten Percent Thief by Lavanya Lakshminarayan. Wish I Was Here by M John Harrison. The Seers by Sulaiman Addonia. I’ve been lucky enough to dip into forthcoming books by Vijay Khurana and Laura Grace Ford that are really exciting. Any book that is inventive, expands or messes/plays with the medium, any book that doesn’t involve relationships in universities or disintegrating bourgeois marriages. I get into trouble every time I recommend books because I inevitably forget and leave some out, so I’ll pick one fairly contemporary novel that I think is scandalously underrated. Little Boy by John Smith. I’m mystified as to why this isn’t seen as a modern classic. I came away in that stunned state where you can’t wait to start writing because you’re so inspired but simultaneously you feel like never writing again because what’s the point? It’s that good, and I won’t rest until people know of it.

I really, earnestly, miss your Twitter presence! Your account was a one-stop amusement shop where I could gather knowledge about an existing topic, find something I had never known about or browse through a curated list of maps. What made you quit the platform much before everyone else? And do you miss it?

I think it’s knowing when’s a good time to leave a party. As a young man, I used to be really bad at that. In Ireland, they call it the ‘sesh’ and it can literally last for days. You get sucked into all kinds of debaucheries and must piece your life back together at the end. In Irish folklore, there’s a recurring story of people straying into ‘fairy rings’ and vanishing, and fairies in Ireland aren’t the Disney kind, they’re these mysterious underworld creatures called the Sidh. When you enter a ring, you’re forced to dance with them maniacally in a circle for days and you only escape dancing yourself to death if you’re dragged out of it or collapse with exhaustion. When you return, you might have rapidly aged or have no memory of the experience. I’m convinced this tale, or alibi, came about in Ireland as a result of people being unable to escape the sesh. When I left home twenty years ago, and having lived in different cultures, I became an expert in when to leave the party.

Twitter just wasn’t fun anymore. Everything became contentious, however innocuous the subject. I’ve written articles on how it’s essentially a fallacy engine and I watched too many people I previously admired demean themselves on there and adopt quite extreme forms of sanctimony and solipsism. It seems to be a catalyst for that downward spiral. It encourages people to lose their minds and profits handsomely from it. I don’t believe it suddenly became toxic when Elon Musk took over, though I’m not a fan of his. It was always bad, however useful or entertaining. I had a few unpleasant experiences on there with stalkers and threats to my family and myself, sectarian and homophobic insults and so on. I can handle myself, growing up where we grew up, and took it on the chin. What I didn’t like was the way the threats were casually dismissed by those who worked for Twitter at the time, pre-Musk. So, I left and, though there are people I miss who I’ve lost contact with (M John Harrison, Elsa Bleda, Ewan Morrison and others), it was one of the best things I ever did.

I came of age as the internet was really started to get going and it was still this expansive utopian wonder machine seemingly created by people who played Myst, dropped acid, followed the Grateful Dead and read the Earthsea Cycle. Or so it seemed in my imagination. And deep down, part of me still believes that or wants to. So, when I see it being narrowed down, commodified and its participants essentialised, until it becomes just a village square with noisy market stalls, squalid entertainments and someone in a pillory every day having rotten vegetables thrown at them, it’s time to hit the road. But the temptation is always there to take part. There are plentiful rewards. I know people, some friends, who’ve used Twitter to springboard into lucrative podcasts and television programmes and good luck to them. It’s just not what I’m interested in doing with my life, at this stage. I mistrust the replacement of the physical world with the virtual. We lose things as well as gain, when that happens. ‘Touch grass’ is an obnoxious cliché but there’s something in it, and I value projects like The Analog Sea Review that encouraged people back to tangible things and places and each other. A friend of mine works in film and he lives in a fairly remote part of Ireland, on a wild shipwreck coast, and when I go to stay with him, we hike over the mountain and down into a fishing village and the conversations we have along the way are unreal, and the weak part of me thinks, ‘This would make a great podcast, people would love this’ and the better side of my conscience thinks ‘Never do that. Just inhabit the present and be grateful for the friendship and connection and the sky and the sea and that mad ram eyeballing us and the bog we are trudging through and that Ice Cold In Alex beer waiting at the end of the trek, cause this is what’s real.’ There’s something beautiful about having moments that are ethereal and will never be repeated and don’t have to be monetised or publicised or even known at all by the wider world. Moments that belong to us and no one else, moments beyond egocentrism and the eternal capitalist hustle.

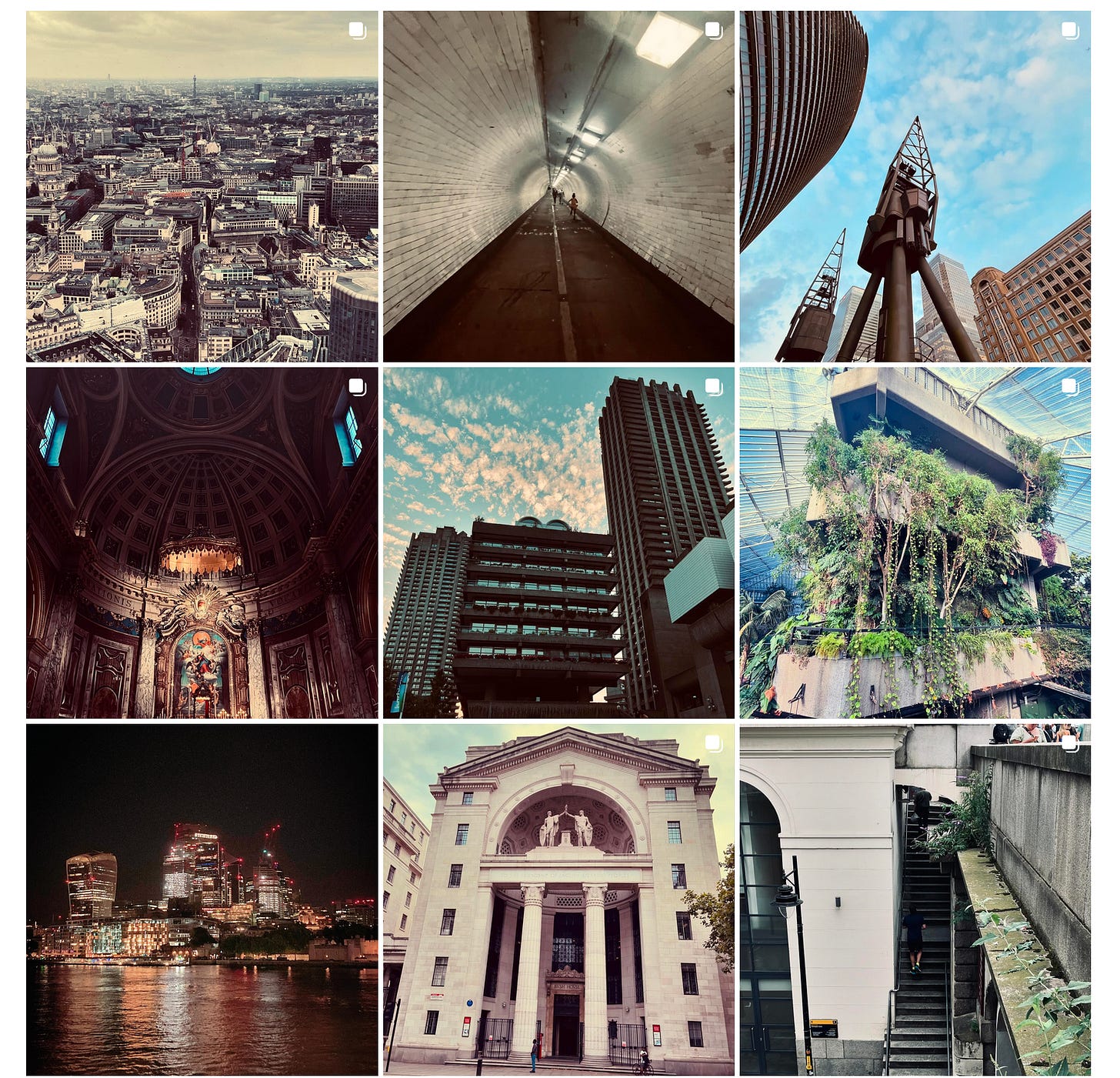

On your instagram you put together a curious feed of streets, corners, back alleys, doors, statues, pubs, and other such seemingly daily knick knacks that can be seen as mundane by many others. I’m never able to stay on it for more than a minute, unless I’m scrolling through your or Lauren Elkin’s feeds. What is your relation to the app?

That’s most kind and it’s a pleasure to be compared with Lauren, who is a friend, a fellow traveller in terms of cities, and whose writing I highly admire. I’m deeply suspicious of all social media, as you’d suspect by now, but I’m also a massive hypocrite. I do think it’s changed people and not for the better. I’m only half-joking when I say the internet was a mistake, a wrong turning for humanity. Yet sometimes I remember how it was before, I was a teenager on the other side of the digital chasm, and conversations like we’re having now, a great distance from each other, were impossible. A friend or relative would move to a different country and you’d never hear from them again, like they’d left the planet. So, it’s wonderful to utilise what superhuman tools you can, to expand our reach, while bearing in mind there’s always unseen costs and risks. The internet’s not just a tool. It’s a kind of virus. And Instagram is pure vanity, of course, but it’s also a valuable visual diary. I have a strange kind of memory that is very spatial. I can walk around rooms in the past and see everything and everyone in them but I’ve no sense of chronology or any feeling of having done or achieved anything even though my schedule is insanely busy and I’m always on the move. There’s neurodivergent things there that I’ve been avoiding or trying to transmute into gold; I’m great with space and horrendous with time. I think Instagram helps me orientate. I can come back and see things in order and context. It provides a kind of arc or an order. Otherwise, I’m just endlessly drifting. It’s also my way of fooling myself into thinking there’s a purpose behind any of this, and we all need our illusions.

I came to know pretty late that you were in India (Mumbai) sometime last year. Had I known, I’d have travelled to meet you and get my books signed. Although I don’t know Mumbai well, but I could’ve shown you around a couple of my favourite places (spaces and building wise) there.

Can you talk about your India visit? Anything that stood out for you during that?

Everything stood out. I can see why they call Mumbai ‘Maximum City’. I used to work off Oxford Street in London and it’s chaos especially around Christmas but I’ll never think of London as being especially busy ever again. Mumbai is intense. I adored it and will return to the country, god willing. I have a map of places I want to explore while I still can and there are so many in Rajasthan, let alone the rest of India. I went to Mumbai for two projects I’m working on – one on empire and the other on urban writing beyond the West. I had the good fortune of being told where to go by a dear friend of mine - Taran Khan, author of one of the great contemporary urbanist books Shadow City: A Woman Walks Kabul. I also spent time exploring the streets with another incredible writer Saumya Roy, author of Mountain Tales: Love and Loss in the Municipality of Castaway Belongings. In the end, there was too much material; I’m still sculpting it down. If there’s one image that’s stayed with me, it’s breaking away from the crowds into a quiet part of Fort, and sitting on steps near one of those mysterious Zoroastrian Fire Temples with those amazing Lamassu stone gods guarding it, and spending an hour just drinking lemonade and watching vultures circle overhead. Or Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Terminus at dusk like this huge gothic spaceship has landed in the city. Or the soundtrack of the streets, so alive, all through the night. I think part of me is still there.

I know you are working on a book next that you lost in its entirety because your laptop was stolen. Can you share something about it?

Well, that was self-inflicted. I’m perpetually distracted and left it behind in this exquisite old Art Deco cinema. I realised within five minutes and ran back but it was already gone. London is pretty merciless that way. Things vanish. There’s a whole Sargasso Sea beneath the city full of stolen goods. Losing an entire manuscript would have been torturous when I was younger but I don’t feel that way any more. Maybe something in me has died but I just put it down to fate now. It wasn’t meant to be. It is what it is. I’m the least stoical person imaginable but I’ve always liked the stories of the Ancient Chinese poets in the mountains, carving writing onto rocks and trees, knowing the elements would eventually erode them. There’s a peace in reconciling with that. Nothing lasts forever.