Certified Copy: Reading in translation

#Scurf215: On reading Olga Ravn, Vigdis Hjorth and Tove Ditlevsen only in translation, and Geetanjali Shree in both avatars

Lately, I’ve been reading the work of a few (three) Scandinavian (women) writers. I do realize that I’m reading these poems, essays, novels in translation. They’ve originally been written in languages — Norwegian, Danish — that I’ve very little to no access. I read them thanks to the hard working translators who put in day and night, go through months, sometimes even years, translating these works to satisfy various parties — the original writer who might or might not know the English language very well, the publishers and finally, the readers (some of who will read the text in both the iterations).

In the last decade we’ve all been alerted to the whole literary debate on how translators play a major role in getting the work of many foreign language writers out in the world so that more and more of us can find these books. Considerations involving the work of translator Jennifer Croft, who translates the Nobel Prize-winning Polish novelist Olga Tokarczuk, and that of Deborah Smith who works on translations of Nobel Prize-winning South Korean writer Han Kang, have stayed with me.

In 2022, after Geetanjali Shree won the International Booker for Tomb of Sand (translated by Daisy Rockwell) a similar conversation caught fire. It was one of those rare occasions when I had access to both the languages this mighty book had been written in — Hindi and English — and stirred up emotionally, I had resolved to read both of them. I wanted to know how translations worked. I embarked on that adventure and soon found myself overtaken by strong emotions stemming from my return to the Hindi language. Ret Samadhi (Tomb of Sand’s Hindi title) in its original, raw, and perhaps foremost felt like a punch in the gut. From that visceral opening chapter I knew that while Rockwell had done a fabulous job, reading Ret Samadhi in its original rendering felt like a homecoming. The flavor of those turns of phrases, the satire, the salty zingers… uff… none of that could be captured as well in another language. And yet, what Rockwell had given us in the form of Tomb of Sand was a page-turner, was a stunningly powerful feat of literary writing and was exultantly the International Booker Prize winner!

Along these lines, a recent essay by Toril Moi in the London Review of Books touches on instances of translation and how sometimes it can tinker with the original source text and the subtle, sometimes not so obvious, meanings that undergird the text on the page. She writes about leading Norwegian novelist, Vigdis Hjorth’s novel If Only released in its English translation by Verso Books. As much as I am grateful to the translation of Charlotte Barslund, who has also translated various other books of Hjorth, Moi’s essay had me pondering about those very vital nuances that I first encountered while reading Tomb of Sand in both Hindi and English.

📚 London Review of Book: I must divorce; Toril Moi

In her essay, Moi writes:

“In her English version of If Only, Barslund, a translator I usually admire, tends to sacrifice conceptual accuracy to colloquial fluency. The effect is to mask the seriousness of the existential issues at stake.”

Moi refers to parts of the text where the “philosophical resonances of the original” are sacrificed at the altar of playing to the gallery. She elaborates on this bit in the LRB podcast (where, by the way, she’s a delightful guest to listen to!), driving home the point that while a translator might (in most cases) have the best intentions for a work, sometimes the popular notions around the writer, or the genre, or just the geography they’re from, might colour their approach. Read this bit to get a clearer sense of this:

I’m currently reading Hjorth’s If Only and find myself unable to move past instances where the text just is too opaque. It doesn’t seem to bring out the nuances or the intended subtext that might’ve come across immediately to the reader of Om Bare (If Only, in Norwegian). When asked about how satisfied she is with the work of her translator in 2023 by the Intenational Booker committee (Hjorth’s Is Mother Dead was longlisted for the International Booker Prize 2023), she said: “I have been working with Charlotte for several years and I have come to trust her fully. I am sure she will always find the right voice for the English editions of my books. I respect her independence and her choices… . I can’t rate her English myself, but everyone says it is excellent. I believe them, of course! I want to reiterate that I trust her completely and I am so happy to have her as my translator.”

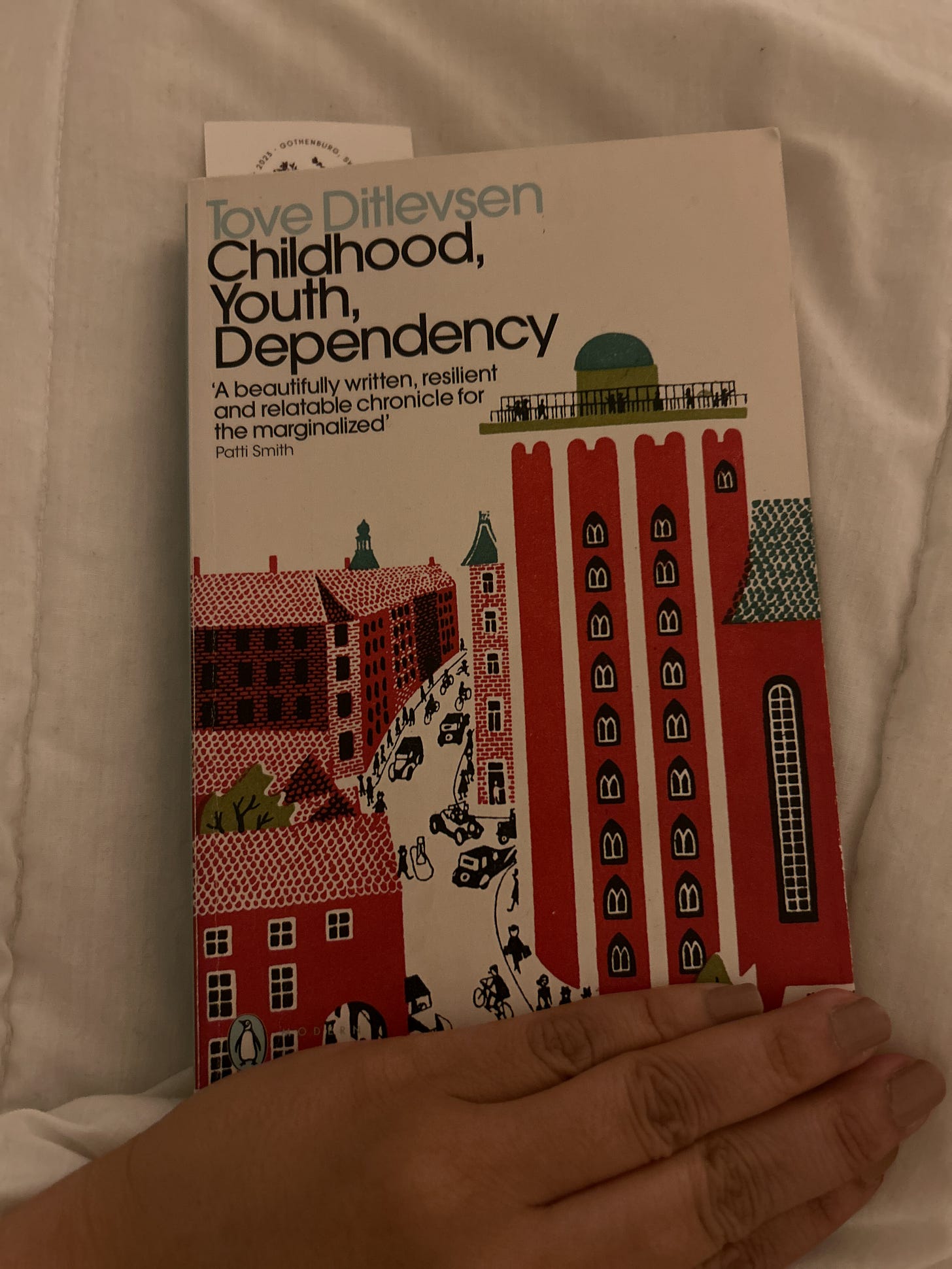

This brings me to another recent essay, in The Paris Review, by leading Danish writer and poet Olga Ravn writes extensively about the world and works of another Danish poet, writer Tove Ditlevsen. Having read both of their works in English, I was once again faced with the Sisyphean quandary of wanting to read both their works in their original Danish forms.

📚 The Paris Review: The Image of the Doll: Tove Ditlevsen’s Worn-Out Language; Olga Ravn

Writing about Ditlevsen’s language, Ravn writes:

What I’m trying to say is that some of Tove Ditlevsen’s poems work deliberately with worn-out language, with sentimental language. With the corset. With the cliché. It’s the voice of Eve in “Eve,” who says: “That’s why my mouth has wilted, it has kissed too many men, / it has sung too many songs, it will never sing again.”

The minutiae of everyday, those minute cultural nuances, the veritable turns of phrases that would be hair-raising, gasp-worthy or even just completely mundane, get absorbed in the vastness of the rest of the text in their translated forms. We get an overall idea, but the meaning sometimes isn’t fully conveyed. And that I feel is the beauty of reading and mining for meaning. It is to try to grasp at the straws of what we make of these stories inside our heads, and then to travel with them, swirling them over and over again like two-day old laundry until the mush yields itself into something more than the sum of its colorful parts. That’s how I read most of my books anyway — even those that I’ve access to in their original language.

This brings me back to a para from the New York Times review of Kiarostami’s Certified Copy (2011).

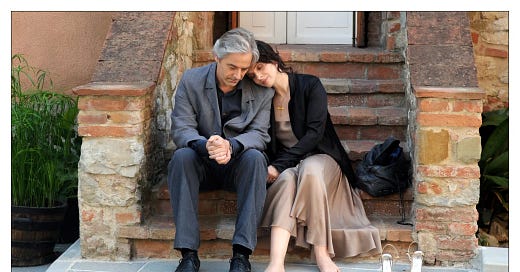

Certified Copy Abbas Kiarostami’s first feature film made outside his native Iran, is such a conspicuous leap from neo-Realism to European modernism, it sometimes feels like a dry comic parody. As the movie goes along, it begins to deconstruct itself by posing as a cinematic homage, or copy, if you will, of European art films of the 1950s and ’60s, with contemporary echoes.

In Certified Copy, Kiarostami, known otherwise for his “Iranian cerebral-ness” breaks out of character and makes film about an intellectually charged romance that revolves around the metaphysics of identity (this idea was crudely hinted at in a recent raved about, internationally loved Indian film). Critics at the time had been thrown off guard by the European and almost un-Kiarostami-esque sensibilities of the film. They restrained themselves, wrote limited praises in reviews. Yet, in elaborate essays, scholars called it a “masterful contemporary example of the European art film” and, “far more” significantly, it is a fine “work of human philosophy,” connecting it back to the larger body of his work.

Certified Copy (also my favorite Kiarostami by miles) makes me ponder at a premise: what if someone starts watching Kiarostami with Certified Copy as their first film? Wouldn’t they too also ache to understand the “original” of the lot — given how vastly different Certified is from his other (Iran-based) films? Then, is Certified Copy a more Kiarostami movie than let’s say, The Wind Will Carry Us? Perhaps this argument is tenuous and over-wrought, and perhaps it could be that not everything written by a writer will have a single strain running through it. Then does that make every new work akin to a new translation of the work that came before that. That also reaches to what Walk Whitman was getting at when he called himself to contain “multitudes”, and the now Instagram caption-ified Didion quote: “I have already lost touch with a couple people I used to be.”

The double entendre of reading in translation doesn’t end right there. I’ve been thinking about languages and toying with notions around them for years. I’ve also written on navigating through this life of being a Hindi-language speaker who writes and reads almost entirely in English. I was born in a de-industrialised north Indian city, with Hindi as my muttersprache, but studied in English, at the school, university and higher studies levels. I’ve also mostly lived away from home, which meant picking up languages of places I was stationed in, whether for work or studies - snacking on Tamil, Marathi, German and now, Swedish.

The language worm in my brain roams about aimlessly, as I once again set forth on this new adventure of wanting to read these Scandinavian writers in their original. Till then, here’s a review I wrote of Olga Ravn’s The Employees and some more of my essays to keep you company on this -3 degrees Swedish winter night. As the snow glistens outside, I head over to finish reading the last 50 pages of If Only and find a conclusive end to that story, at least in my head.